Beloit is a small liberal arts college in southern Wisconsin, seemingly far from the front lines of the global press freedom battles. I spent a week there as the Weissberg Chair in human rights, speaking to students, faculty, and members of the local community about the threats to journalists around the world. As it happens, my visit to Beloit coincided with a debate over free speech that roiled the campus.

It started when a conservative student group called Young Americans for Freedom decided to invite Erik Prince to give a lecture. Prince is the founder of the private security firm Blackwater, which has been implicated in numerous human rights violations, including the killing of 17 civilians in Baghdad’s Nisour Square in 2007. Prince’s latest proposal is to provide private contractors to replace the US military in Afghanistan. YAF, which has only a handful of members on the Beloit Campus, is a national organization that often courts controversy by hosting provocative speakers.

The massacre of 49 worshippers in Christchurch, New Zealand, on March 15 elevated emotions around the Prince invitation. One student, Nate Acharya, expressed his anguish as a Muslim on a student-administered Facebook page, writing, “To everyone with a basic sense of human decency, let’s organize to repel the March 27th invasion of our college, lest we be complicit in it and all that it represents.” Acharya also re-posted a menacing message from an Islamic State follower, urging colleagues on campus to be aware of the threat and “stay safe.” In another post, he wrote, “Hey if you post on 4chan or [8chan] I don’t care what board you’re part of, you deserve to be shot for knowingly [participating] in one of the biggest breeding grounds for white supremacist terrorists of the modern era.”

The Beloit College administration began an investigation after being alerted to the posts by YAF president Andrew Collins. Collins, who was tagged in Acharya’s original Facebook post, told the Beloit student newspaper that he did not feel personally threatened but “wanted security to be aware of the heightened tensions surrounding the Erik Prince lecture following Christchurch so they could take adequate precautions.”

In fact, the college administration called the Beloit police, and suspended Acharya, requiring him to leave the campus while an investigation was carried out. A group of students rallied to support Acharya, marching on a meeting of the Faculty Senate and circulating a petition stating that Acharya’s posts were “not threatening, nor do they incite violence, which is more than can be said for the ideology (white supremacy) Nathaniel spoke out against.” After carrying out its investigation and holding a hearing, the administration allowed Acharya to return to campus but placed him on probation.

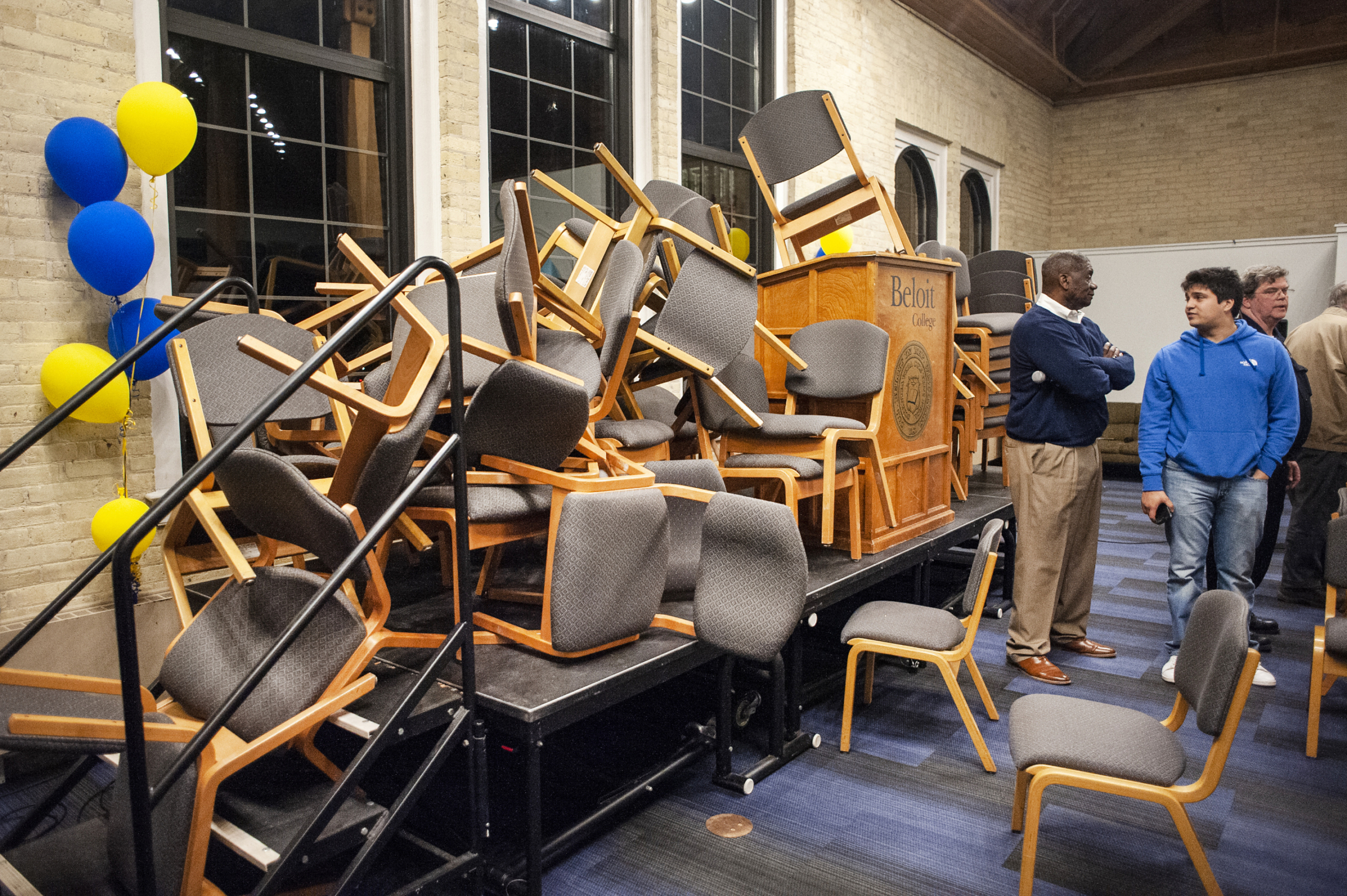

But the debate over Prince’s visit was far from over. While the college administration urged students to find ways to express their disagreement while allowing Prince to speak, anger boiled over. Last Wednesday, a group of students used drums and musical instruments to disrupt Prince’s talk. They piled chairs on the stage.

Erik Prince, founder of Blackwater, was supposed to speak at Beloit College more than 30 minutes ago. So far, protests seem to have delayed that. pic.twitter.com/JarR5EvVlF

— Angela Major (@angela_major_) March 28, 2019

Prince retreated off campus where he spoke to a small gathering of students, declaring in an interview with a local newspaper that the Beloit College president and the administration “lacked the moral courage to enforce free speech and to defend free speech,” adding, “Fortunately, President Trump will defend free speech and I think the college will be hearing from the court soon on this because enough is enough.” Prince was referring to a March 20 executive order signed by Trump that threatened to cut off federal funding to colleges and universities that failed to uphold free speech. In an analysis, PEN America called it “a thumb on the scale for conservative voices on campus.”

For his part, Prince seemed more than willing to stoke the controversy in order to advance a partisan political agenda. (Prince is the younger brother of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos).

In my discussions with Beloit students—one of whom literally jumped out at me from behind a column in order to speak in private—I acknowledged that the cost of tolerating free speech in the digital age can be exceedingly high. The consequences of free speech are no longer just Nazis threatening to march in Skokie, or members of the Westboro Baptist Church screaming insults. Free speech has helped fuel an increasingly toxic online environment full of insults, rumors, screaming pundits, terrorizing images, and active manipulation by governments.

When I asked students if they were prepared to pay this cost, many said no. They perceived “free speech” as protecting powerful, entrenched interests like Prince at the expense of marginalized or vulnerable voices. They wanted to suppress certain kinds of speech—white nationalists, for example—and elevate the voices of the disenfranchised. I asked the students who they would trust to police speech on campus or the wider world. They acknowledged this was a hard question.

Free expression is protected in this country by the First Amendment and around the world by international law. But the legal protections will weaken if the next generation does not value the underlying principle. Those of us who defend free expression—whether on campus or around the globe—need to be able to make the case that free speech ultimately protects the marginal and even radical voices that might not otherwise be heard. Right now we are failing to do that.

Journalists, I believe, have a critical role to play. At Beloit and most other college campuses student groups are granted to right to invite any speaker they wish. But the format matters. A speech, inevitably, elevates the speaker. Instead, controversial speakers—particularly those in the news—should be compelled to answer tough questions from an informed and experienced interviewer, ideally a journalist. This would serve the educational mission, ensuring that the speaker is held accountable and the audience informed. It might even make news. To his credit, Prince recently submitted to withering questions from Al-Jazeera’s Mehdi Hasan.

I spent my week on campus talking about Jamal Khashoggi, Maria Ressa, and other heroic journalists who put their lives and liberty on the line to report the news. Students found their stories inspiring. But I also made the point that when you defend press freedom you are defending a fundamental right. All journalists—the good ones and bad ones, the ones we admire and ones we hate—have the same right to express their ideas.

Beloit College may be a small school in Wisconsin, but the way the students there and at many other colleges and universities across the country grapple with the complex issues of free speech has implications for the rights of journalists around the world. The defense of independent journalists on the front line depends not just on legal protections, but a shared belief of the inherent value of free expression. We need the next generation on our side. Right now, we don’t have it.

This piece has been updated to clarify that PEN America published the analysis on the executive order.

Joel Simon is the founding director of the Journalism Protection Initiative at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism.