The verdict came down in the first defamation case stemming from Rolling Stone’s famously flawed investigation about college rape on the Friday before Election Day.

Now that the electoral shock has ebbed, it’s time to give the results a second look.

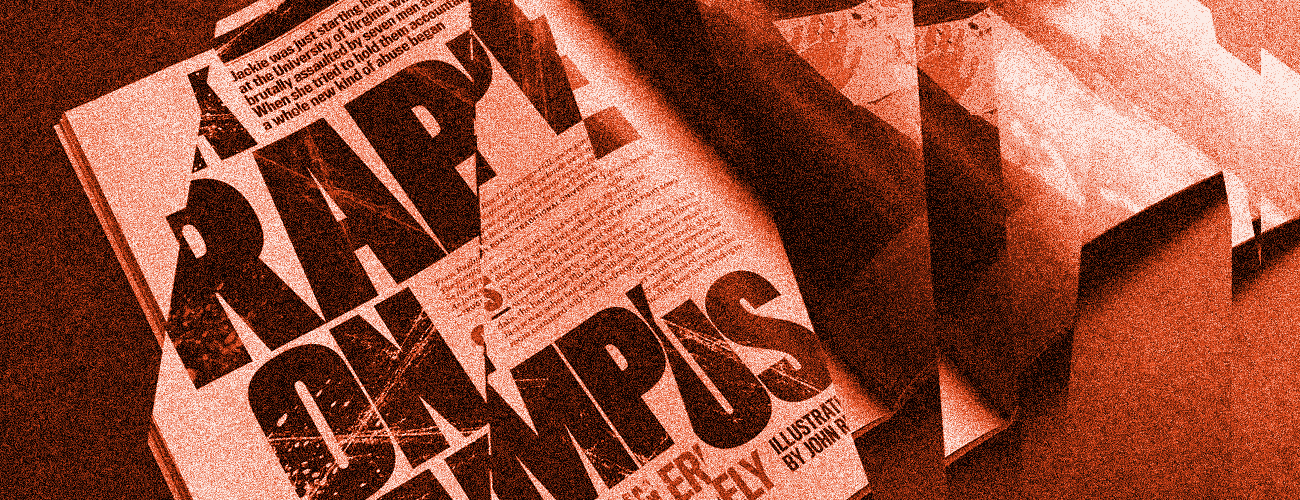

In this case, a former associate dean at the University of Virginia, Nicole Eramo, charged that the magazine and reporter Sabrina Rubin Erdely had defamed her in its much-noted 2014 article, “A Rape on Campus.” That story began with a hard-to-read scene—now acknowledged to have been invented—of a first-year student being violently gang-raped for three hours by seven men at a UVA fraternity in 2012. The remainder of the article took a harsh look at how the university responded to sexual-assault allegations in general and Jackie’s own story in particular. (“A whole new kind of abuse,” as the article’s subhead put it.)

The story was challenged almost immediately after it was published—in The Washington Post, Slate, and elsewhere. Rolling Stone requested, and got, an independent report overseen by the Columbia Journalism School. This damning document found that the magazine’s editing processes were woefully faulty in publishing the piece. Most crucially, the writer and the magazine’s editors went too far in respecting the wishes of a woman they felt had been traumatized by the experience, and did too little to verify her tale.

Writer Erdely didn’t interview Eramo, either—the administrator was prevented from discussing the personal affairs of students—but Eramo loomed large in the latter part of the story anyway. Settlement talks went nowhere. In the end, the jury awarded Eramo $3 million in damages: $1 million from Rolling Stone and $2 million from Erdely. A second lawsuit, from the fraternity itself, is scheduled for trial in Virginia state court next fall.

Here are some takeaways from the Eramo decision, based on insights from lawyers who followed the case.

1) The little things matter

On the jury instruction forms, you can see that the magazine was held liable for just a few sentences. (The writer is on the hook for some other statements, as well; see below.) For example, at one point the report said,

“Lots of people discouraged her from sharing her story, Jackie tells me with a pained look, including the trusted UVA dean to whom Jackie reported her gang-rape allegation…”

The sentence on its face is possibly true—Jackie apparently did tell the reporter that, presumably with that pained look—but Erdely took Jackie’s word for it. The judge instructed the jury that these were factual assertions. The jury found the passage was actionable—i.e., that it was untrue—and that the magazine had operated recklessly by publishing it.

Another passage is a scene in which Jackie tells Eramo that she’s heard from two other women who were gang-raped at the fraternity. Jackie is said to be disappointed at Eramo’s “non-reaction,” which didn’t include “shock, disgust or horror.” This, too, the jury found both actionable and reported with actual malice.

Note that in the first passage Jackie refers to Eramo as “trusted.” The then-dean is in fact presented in a relatively favorable light throughout the story. But that context doesn’t matter when it comes to other statements deemed untrue.

To make matters worse, Eramo testified that she had not been contacted by the magazine’s fact-checkers to confirm the things she was quoted as saying.

2) Jann Wenner just doesn’t get it.

The legendary magazine entrepreneur founded Rolling Stone in 1967 and turned it into a journalistic touchstone, based on both acute cultural insight and a lifelong dedication to strong reporting. Over the years he’s led a host of troubled ventures, but has persevered and now runs a small empire—Wenner Media—that includes US and Men’s Journal. (Perhaps anticipating a heavy libel verdict, Wenner sold 49 percent of his company to the son of a Hong Kong billionaire just a month before the Eramo decision came down.)

But Wenner’s authority failed him when he took the stand in the Eramo case. News reports of his videotaped deposition at the end of the trial’s second week contained many questionable assertions. “We did everything reasonable, appropriate, up to the highest standards,” The New York Times quoted him as saying. “The one thing we didn’t do was confront Jackie’s accusers [sic] — the rapists.” This view of the magazine’s culpability is contradicted by the Columbia Journalism School report, which detailed many other flaws in the magazine’s handling of the story.

The Times article went on, “Mr. Wenner said there was nothing a journalist could do ‘if someone is really determined to commit a fraud.’” Here again, simple checking of the story—talking, for example, to the friends Jackie had supposedly met the night of the supposed assault—would have brought the magazine back from the brink.

Most damagingly, Wenner testified that the full retraction the magazine eventually made was “inaccurate.” He was trying to make the case that, Jackie’s story aside, he thought the reporting on how the UVA administration handled rape cases was substantive. There’s a strong possibility the jury viewed this as a half-hearted retraction, which could have been used as evidence of actual malice.

3) Reporters need to be careful on the podcast and PR trails.

The jury found several passages in Rolling Stone‘s article defamatory. Erdely’s culpability went further, to include an assertion she’d made to WNYC radio host Brian Lehrer, another on a Slate podcast, and a third in an email to a Washington Post reporter while promoting the piece. To Lehrer, Erdely said that Jackie said she’d been “brushed off” by the administration and that the university had “done nothing” when Jackie told them her own story, and further “did nothing when she told them about the other assaults.” She said essentially the same thing on the Slate podcast.

This kind of secondary speech–talking about your story on other media–is rarely a subject of newsroom discussion, but reporters talking up their stories elsewhere often overstate their findings. Says one libel lawyer: “I see this daily in my practice.”

From a legal standpoint, the magazine’s fate, and Erdely’s, were essentially sealed when the judge ruled early on that these were “factual assertions.” An appeals court may rule they are statements of opinion, which would alter the legal calculus.

4) Republication Is a Thing.

Rolling Stone first posted an editor’s note on top of the story acknowledging questions had been raised on Dec. 5, 2014, three weeks after “A Rape on Campus” was published. The note said that Jackie had misled Erdely and that the magazine had misplaced its trust in the first-year-student. The note was immediately criticized, and it was revised the next day to include the words, “These mistakes are on Rolling Stone, not on Jackie.” In April, when the Columbia report was released, the magazine retracted the story and took it down. (The story is still readable through the magic of the Wayback Machine.)

In many ways, this was a transparent approach, and one in keeping with internet protocols, which is often to leave a flawed story up with a prominent note alerting readers what was wrong and why.

But the judge and jury here found that appending the editor’s note to the story without retracting it fully (and presumably taking the story down) constituted a “republication.” Juries can find in half-hearted retractions evidence of actual malice. The jury result forms in the Eramo case show that the jurors did not find the magazine liable for the original publication but did find it operating with actual malice in the republication. In other words, what is seen in the journalism world as a laudable transparency may in certain circumstances turn out to give a defamation plaintiff just enough rope to hang you.

Will this be adjudicated if the case is appealed? Yes. Is it something publishers should be worried about right now? Yes.

This part of the decision seems to have already had an impact, at least at Rolling Stone. In October of this year, the magazine’s website published a lengthy rant about how the NBA commissioner was handling the case of star Derrick Rose, who was facing a civil lawsuit over an alleged gang rape. (Rose won the case.) The piece was taken down two days later. In an editor’s note, the magazine explained that the story had had “substantial flaws“—but gave no further information. Thus endeth transparency.

5) Rolling Stone may be headed for a legal woodchipper

Eramo’s case can be seen as a sideshow to the main failure in Rolling Stone‘s account, which was taking Jackie’s made-up rape story at face value and portraying the fraternity as a haven for sexual violence without doing due diligence to ascertain whether the claim might be true.

And for a number of reasons, Eramo’s case wasn’t a slam dunk. In legal terms, she was a “limited purpose public figure”—someone who would be treated as a public figure for the purposes of the case. In libel law, public figures have to meet the high standard of showing “actual malice,” defined generally as a “reckless disregard for the truth,” on the part of the publication. Eramo was the university’s point person for sexual-assault cases on campus, and had appeared in local media representing the university. The judge in the case noted that she had easy access to the media to defend herself and the university’s actions.

The story of a female student who says she’s been raped and that her story wasn’t taken seriously by her school is the sort of serious public matter the free press is supposed to pursue, and the high bar for libel is designed to let journalists make mistakes doing so. The judge even explicitly told the jury that failure to investigate—the story’s main flaw—was not by itself an indication of actual malice. The magazine’s editors testified that they had not harbored doubts about it before publication—another key test for “actual malice”—and its lawyers argued that criticism of the university’s handling of sexual-assault cases was a matter of opinion, another protected area for the press. Despite all that, the jury found a $3 million liability for what amounted to a glancing blow at a bureaucrat who was in many ways portrayed sympathetically.

The next jury will hear about a full-bore invented account of a violent group rape—stretching over nine long paragraphs—committed by a local institution that, in high contrast to the Eramo section of the story, the magazine did virtually nothing to corroborate. In a nightmare scenario for Rolling Stone, each of the three friends Jackie consulted the night of the alleged attack might demonstrate how a single phone call from Rolling Stone would have undermined Jackie’s story.

The fraternity will likely be found to be a private, not public, figure. The standard for defaming a private figure is much lower than for a public one—simple negligence, which has already been clearly shown in the Columbia report, not actual malice. The university shut the house down; its building was vandalized, and its members were hounded on social media and smeared by association with an institution that was said to be a regular host for gang rapes.The fraternity is asking for $25 million in compensatory damages for general reputational harm.

The Eramo decision “certainly should embolden” the fraternity’s lawyers, said Eugene Volokh, a UCLA law professor who has followed the case for the Post.” Don’t be surprised to hear that the magazine, or its insurance company, is trying to settle.

Bill Wyman is the former arts editor of NPR and Salon.com. Follow him @hitsville.