The State of the Union is antique.

That’s not what President Barack Obama will tell a joint session of Congress on Tuesday night, but it is how new media organizations have treated this year’s annual address. The collective shrug started with Vice News, which didn’t publish any previews of the speech. Mic and Vox both outlined White House policy proposals released in previous weeks — detailed sneak peeks that typically wouldn’t have been given to news outlets decades ago — while the latter’s coverage Tuesday focused on the administration’s digital media strategy, State of the Union history, and what Obama “might say if he had a few drinks first.” BuzzFeed, which boasts a comparatively robust Washington bureau, tipped its cap to Obama’s YouTube-star-studded interview lineup following the speech. But Editor in Chief Ben Smith doesn’t buy the State of the Union as a platform to float policy balloons.

Interesting internal email thread about whether we have to cover no-hope SOTU proposals that exist solely to be written about

— Ben Smith (@BuzzFeedBen) January 18, 2015

Indeed, just 41 percent of policies requested in the speeches since 1965 have seen full or partial enactment, according to research by political scientists Alison Howard and Donna Hoffman. Obama’s success rate is a paltry 30 percent, and this year, he faces a Republican-controlled Senate for the first time. “With his second to last State of the Union, President Obama will be slinging a Hail Mary toward the end zone,” Tim Mak writes at The Daily Beast. “Sadly, no one will be there to receive it.” No small wonder, then, that the cool kids on the digital block won’t acknowledge this old-school Washington pageantry.

But they’re not alone in displaying apathy. The tenor of mainstream coverage is slowly but surely following suit, with more outlets including caveats in their coverage as to how ineffective the speeches are for initiating policy change. Commentators across the spectrum this year have called for cancelling it entirely. And reporters have framed the one-night event as a glimpse at 2016 election themes, a rhetorical exercise, or a political formality rather than a can’t-miss event for unveiling a policy agenda. (A handful of outlets still previewed the address as if it carries substantial political weight.)

The address isn’t just unable to impact policy. It also does little to influence public opinion — data that news outlets are increasingly considering — though some insiders, pollsters, and academics have been saying so for years. “In particular, the evidence is clear that presidents don’t tend to get a ‘bounce’ in approval levels from the [State of the Union],” political scientist Brendan Nyhan wrote for CJR in 2012. “These findings reflect a more general misperception. Despite what many reporters believe, the president can rarely change public opinion on domestic policy with this or any presidential address.”

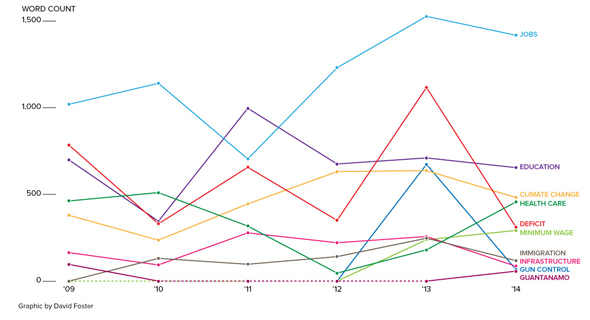

Priorities The number of words Obama has dedicated to various policies in his annual addresses. (David Foster / Politico)

What’s more, the one-night event’s television audience has continuously withered in each of Obama’s years in office. Though last year’s address was carried by 14 television networks, its 33.3 million viewers were the fewest since Bill Clinton’s final State of the Union in 2000, according to Nielsen.

The White House has attempted to staunch the losses by teasing out the speech’s major policy proposals over the past few weeks, essentially reversing the whistle-stop tour traditionally taken by presidents to drum up support afterward. The White House has also used proactive social media outreach to maintain an audience, often circumventing political reporters in the process.

Obama’s January 8 proposal on Facebook for free community college tuition garnered 8.3 million views, while Senior Advisor Valerie Jarrett’s LinkedIn announcement of a paid leave initiative drew more than 385,000 readers. On Thursday, the president will sit for interviews with three YouTube personalities — a comedian, a makeup reviewer, and a professional nerd — whose combined subscribers total nearly 14 million people.

The latter move drew the ire of the White House press corps last week, with two questions at Thursday’s press briefing addressing the topic. “These folks who are going to be conducting these interviews are not professional journalists—they’re people who post videos on YouTube,” CNN’s Jim Acosta said. “And I’m just curious, was ‘Charlie Bit My Finger’ or ‘David After Dentist’ not available?”

White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest replied that the new PR focus wouldn’t replace more traditional media outreach. He added, “this is part of an integrated communication strategy to make sure that the American people understand exactly what the president is fighting for in Washington, DC.”

That “integrated communication strategy” is further evidence the televised speech itself is an outdated form, one designed for a vastly different media environment. Harry Truman’s 1947 address was the first to be televised, and in 1965 Lyndon B. Johnson pushed the remarks from the afternoon to primetime for a larger television audience. With that audience now shrinking, and with the White House adopting new tools to share its agenda, reporters might do well to avoid focusing on a single night each winter.

“We have the speech because it is Tradition, and that Tradition reflects the Importance of the Office,” The Washington Post’s Philip Bump writes. “So Obama walks onto the House floor, passing through an effusive crowd of legislators as they imagine themselves making that same walk, and the Great Spectacle of Washington is upheld.”

David Uberti is a writer in New York. He was previously a media reporter for Gizmodo Media Group and a staff writer for CJR. Follow him on Twitter @DavidUberti.