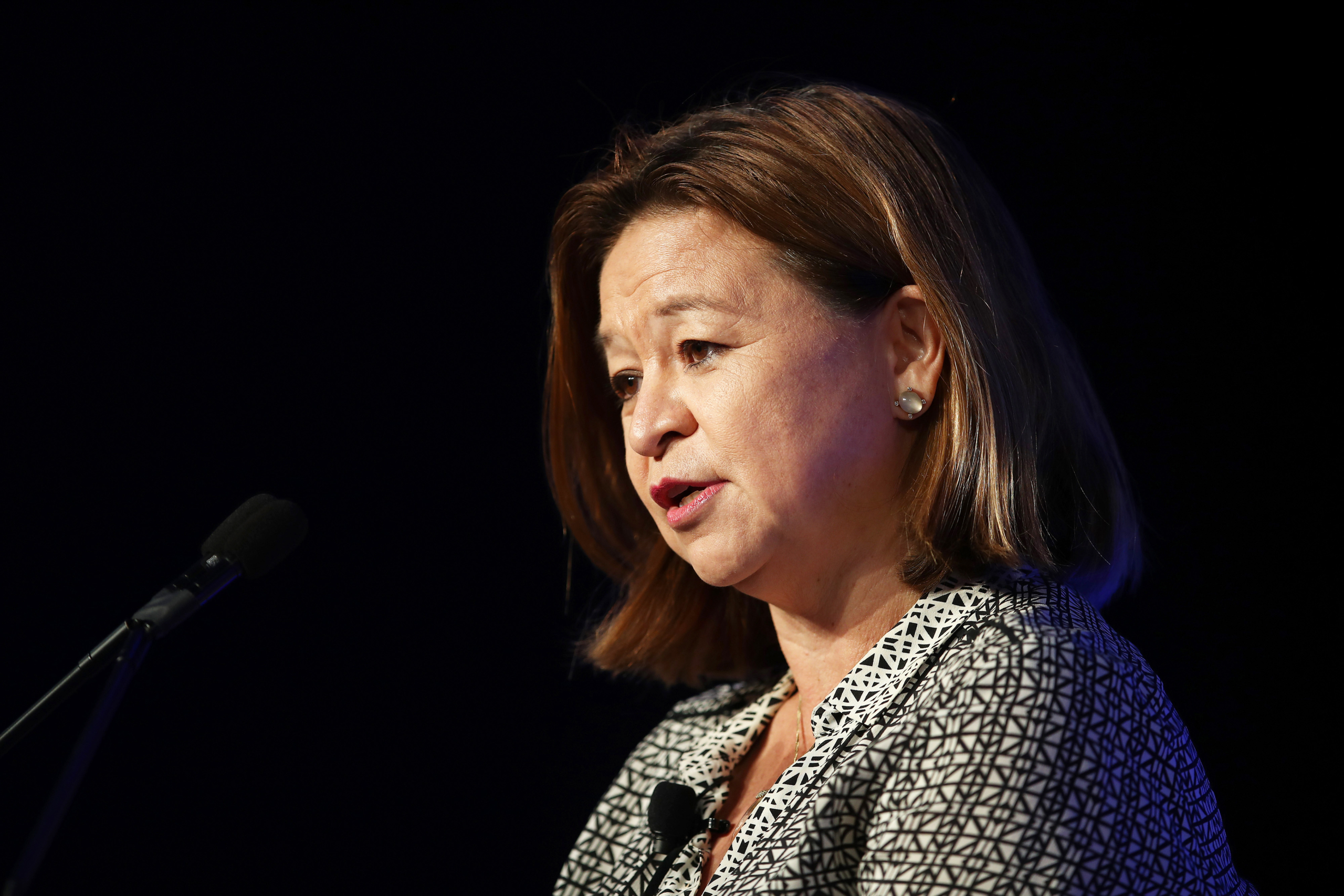

On September 24, Michelle Guthrie, the managing director of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, was sacked by the public broadcaster’s board—just halfway through her five-year term. The ensuing fallout led the Australian news cycle for days.

Some journalists on the ABC’s staff initially rejoiced at the announcement of Guthrie’s firing. In a tweet, the executive producer of one of the country’s most respected investigative news programs, Four Corners, described the move as an “excellent decision.”

Excellent decision https://t.co/Xzo14iRDcM

— Sally Neighbour (@neighbour_s) September 24, 2018

But it soon emerged that the impetus for Guthrie’s removal wasn’t as straightforward as replacing an ineffectual manager. Emails obtained by the Sydney Morning Herald suggested that Guthrie had been standing up to the chairman of the ABC’s board, Justin Milne, to protect the broadcaster’s legislated editorial independence. The possibility of political meddling at the ABC sparked outrage, and Milne soon resigned as well.

The Australian government ordered a departmental inquiry into the events surrounding Guthrie’s sacking. The report, which was released Monday, confirmed that Milne had emailed Guthrie urging her to fire an ABC journalist whose reporting was critical of the government. That email was sent at a politically sensitive moment for the government, which was trying to sell its budget to the Australian people.

The Guthrie/Milne situation suggested there was a potentially troubling deference to government interests among members of the ABC board. In the aftermath, the ABC must not only rebuild its executive leadership, but reassure Australians who might have lost confidence in the organization that it is back on track.

Guthrie’s appointment as managing director was met with mixed reaction when she joined the public broadcaster in May 2016. Previously an executive at Google who was based in Singapore, Guthrie was tasked with leading the ABC in the digital era. But her reign coincided with a difficult period for the organization. Australia’s 2018/2019 federal budget, released in May, saddled the ABC with a funding freeze, at a cost of $84 million Australian dollars. Previous funding cuts in 2014 had resulted in the elimination of 1,000 jobs at the broadcaster.

Efficiency measures are rarely popular with staff, and Guthrie had to figure out how to service an increasing number of digital formats with less money to do it. The ABC’s flagship radio current affairs programs, PM and The World Today, were halved in length. Lateline, the network’s highly respected nightly TV current affairs show, was axed.

Yet some of Guthrie’s wounds were self-inflicted. Soon after she started, she reportedly told a meeting of Four Corners investigative journalists that they “should be doing more positive profiles on successful business leaders.” Meanwhile, a 2017 ABC staff survey showed morale down, and ABC radio veteran Phillip Adams said Guthrie had introduced “managerial nonsense” at the broadcaster.

ICYMI: The FBI’s secret investigation of a journalist

Milne cited leadership issues as the reason for Guthrie’s sacking. “The board felt in the end her leadership style was not the style that we needed going forward,” he told ABC News. “We needed a different leadership style and that is the decision of the board.” This seemed to make sense to some ABC staff, who said Guthrie didn’t understand journalism, and rarely watched the news.

But Guthrie said her dismissal was unjustified. “I am devastated by the board’s decision to terminate my employment despite no claim of wrongdoing on my part,” she wrote in a statement. “At no point have any issues been raised with me about the transformation being undertaken, the Investing in Audiences strategy, and my effectiveness in delivering against that strategy.”

The ABC employs 4,300 people across Australia. It is a key provider not only of national radio, television, and online news services, but also local news services in regional areas. Like the BBC in the United Kingdom, the ABC is affectionately nicknamed “Auntie,” and it was recently found to be Australia’s most trusted news organization.

Although the ABC is entirely government funded, it operates independently. The 1983 Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act outlines the functions and management of the ABC. Under the Act, the managing director of the ABC is appointed by the board, and also holds a seat on the board. Aside from one staff-elected director, the rest of the board—including the chairperson—are appointed by the government.

According to the Act, “it is the duty of the board…to maintain the independence and integrity of the corporation.” That is generally understood to include protecting ABC journalists from political pressure that could influence their reporting.

The ABC is independent of government.

The ABC's funding is not independent of government.

This is the tightrope the ABC's senior management have to walk.

— Ben Nguyen (@ben_syd) September 26, 2018

The ABC has developed an internal process for handling complaints with reference to the ABC Act and the Broadcasting Services Act, which covers complaints from the government about ABC’s coverage of government activities. There have been numerous complaints from the government in recent years about a perceived left-wing bias at the ABC, which have been bolstered an ongoing commentary in conservative media outlets. The ABC’s chief economics correspondent, Emma Alberici, has been subject to a number of them in the past year.

In February, Alberici wrote a news story and an analysis piece critical of the government’s corporate tax policy as it was being shepherded through parliament. The government filed an official complaint accusing Alberici of bias and inaccurate reporting. A subsequent ABC investigation found several errors or omissions of fact in the news story and conceded that some elements of the analysis were misleading. It withdrew both stories, which were later republished with revisions. On May 7, the government complained about Alberici’s reporting on its innovation spending, but the complaints were rejected following an internal review.

On May 8—the day the government released the federal budget—Milne allegedly emailed Guthrie, urging her to fire the reporter. “They fricken hate her…. We r tarred with her brush. I just think it’s simple. Get rid of her. My view is we need to save the corporation not Emma. There is no [guarantee] they”—referring to the Liberal Party, currently in power—“will lose the next election.” Guthrie refused to comply.

There were other suggestions that Milne was lobbying in favor of decisions that would make the government happy. He allegedly told Guthrie in a phone conversation to “shoot” ABC Political Editor Andrew Probyn after Probyn, in a 2017 news report, called former Prime Minister Tony Abbott “the most destructive politician of his generation.” (The comment was later identified by the Australian Communications and Media Authority as a breach of the ABC’s impartiality rules.)

Milne also allegedly advised Guthrie against changing the date of an ABC music countdown, the Triple J Hottest 100, that is usually broadcast on Australia Day. At the time, public sentiment was beginning to shift in favor of changing the date of Australia Day out of respect for Indigenous Australians, but the government was opposed to the idea.

In a press statement, Milne wrote: “I have never been directed by any member of parliament to seek the sacking of an ABC staff member, nor have I ever directed ABC management to sack a staff member.” Communications minister Mitch Fifield and former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull also denied any interference.

The outcry among ABC staff, the public, and other members of the media was swift and loud once the contents of Milne’s email to Guthrie about Alberici was published.

The government ordered a departmental inquiry to sort out what had unfolded. “It is important for the community to have confidence in the independence of the ABC,” Fifield wrote in a press statement. Impromptu meetings were held among hundreds of ABC staff at ABC bureaus in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane on September 26—the day Milne’s emails were first reported. Staff voted by show of hands for Justin Milne to step aside amid the investigations. The journalists’ union—the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance—also called for Milne to quit.

Even right-wing news commentators, who are typically hostile to the ABC, came out in support of the ABC’s independence and Guthrie’s defense of Alberici. In a September 26 column for the Herald Sun, conservative commentator Andrew Bolt wrote, “This kind of political calculation is disgraceful. Shame on the board for not quashing it immediately. Milne must go.” (Bolt has long been hostile to Milne for, somewhat ironically, refusing to cave to political pressure over the ABC’s editorial output.)

Staff meeting underway at ABC now pic.twitter.com/Vprm7gqCux

— Joe O'Brien (@JoeABCNews) September 26, 2018

After initially vowing to stay put, Milne resigned on September 27. He appeared that night on the ABC current-affairs program 7.30 to answer questions from political reporter Leigh Sales. “Clearly there is a lot of pressure on the organization, and as always, my interests have been to look after the interests of the corporation,” Milne told Sales, “It’s clearly not a good thing for everybody to be trying to do their job with this kind of firestorm going on.”

Guthrie hasn’t commented on Milne’s departure, but she has reportedly hired legal representation and said in her original press statement that she is considering her legal options. A photo of Guthrie lunching with a friend the day after she was sacked took on a new significance in the days that followed. Although it was posted to Twitter two days prior to Milne’s resignation, it seemed to ooze schadenfreude.

Love Rockpool. Love old friends. #Sydney pic.twitter.com/Zy61l4rTWc

— Melanie Brock (@melanie_brock) September 26, 2018

David Anderson, previously the director of the broadcaster’s Entertainment & Specialist division, has now taken over as acting managing director of the ABC while the board searches for Guthrie’s replacement. In a tweet encouraging staff to get on with their jobs and “hold your heads high,” Gaven Morris, the ABC’s head of news and current affairs, added a reminder that “Your bosses are the Australian people.”

To @abcnews staff asking me how to respond to these stories about the ABC, I’ve said this: hold your heads high, look everyone in the eye and get back to your desks, behind your microphones and in front of the cameras and do your jobs well. Your bosses are the Australian people.

— Gaven Morris (@gavmorris) September 26, 2018

But questions remain. Members of the opposition Labor party and the Greens party previously called for the full ABC board to be overhauled, as Guthrie had made the board aware of Milne’s emails prior to her firing, and the board still supported Milne as chairman. Paul Murphy, the head of the journalists’ union, said that merely conducting a departmental inquiry was not enough.

The findings of that inquiry have now been released. While the report acknowledges that Milne sent the email regarding Alberici and that he spoke to Guthrie on the phone about Probyn, it convey’s Milne’s view that he did not consider either communication a directive. The report concludes that no evidence of political meddling at the ABC was found, and that no further action is required. Labor has criticized the government’s report for lack of detail.

The government has now reportedly referred the matter to the Senate, before which Guthrie, Milne, Fifield and even Turnbull could be called to give evidence. As these investigations unfold, the ABC has returned to business as usual, and the news cycle has moved on.

Guthrie was never fully embraced in her role as managing director, but not everyone was happy to see her go. Not only was she the first female managing director of the ABC, she was a champion of diversity in an Australian media landscape that is largely white and middle-class.

No boss is beyond criticism.

But the idea of attacking someone for championing diversity in an aggressively monocultural media landscape turns my stomach. pic.twitter.com/yaXGuC4AtH

— Benjamin Law (@mrbenjaminlaw) September 24, 2018

As the fallout from Guthrie’s departure fades, her replacement will be required to chart a viable course through an unpredictable media landscape. That means doing more with less to build a news organization that’s geared up for the digital era, protecting the ABC’s precious editorial independence, and lobbying a sometimes hostile government for the funding that will keep it afloat. If this episode has revealed anything, it’s what a challenging job that is.

ICYMI: The story BuzzFeed, The New York Times and more didn’t want to publish

Shelley Hepworth , formerly a CJR Delacorte Fellow, is Technology Editor at The Conversation in Australia. Follow her on Twitter @shelleymiranda.