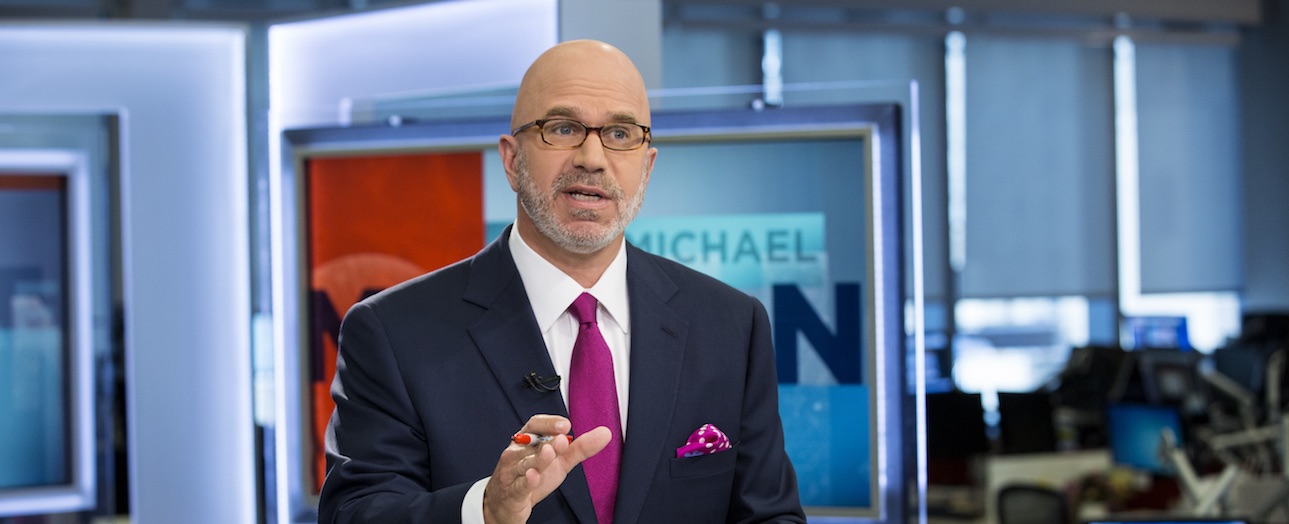

Michael Smerconish, a prominent Sirius XM and CNN host, has enemies on both sides of the aisle. As a relentlessly moderate voice in an increasingly partisan cacophony, he is a unique figure in the current political environment. The longtime Republican, who came of age in the Reagan era and served in the first Bush administration, left the party in 2010, and has occupied what he calls “a partisan no-man’s land” ever since.

His new book, Clowns to the Left of Me, Jokers to the Right, is out this month from Temple University Press. It collects 100 of his columns from the Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Daily News, beginning in the months following the September 11 attacks and running through the early days of the Trump presidency. Not all of the pieces are political, but the ones that are trace Smerconish’s journey from self-described “consistent Republican sound bite” to centrist commentator who feels the party has left him behind in its move to the extreme.

Each piece is reprinted as it ran, with an afterword to reflect Smerconish’s updated views on what he wrote, and he doesn’t shy away from instances when he got it wrong. An early defense of Bill Cosby, for example, receives an extended mea culpa. The eclectic cast of characters who populate the book—from Fidel Castro to David Duke to Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters—make for entertaining reading. But the snapshot of America in the 21st century he offers is one of a country increasingly divided by social and political issues, a trend that he blames largely on a polarized media.

Smerconish spoke with CJR about his political journey, the state of the media, and the dangers of dogmatic ideologues. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You’re in a unique position as a centrist opinion journalist and pundit in the current era, but your background is firmly in the Republican establishment. How did you arrive at this “partisan no-man’s land,” as you call it?

It’s been a very organic process. There was never any plan, and it’s certainly been against career interests. In my business we reward the doctrinaire types, the ideologues, the pot-stirrers.

There was not much of a choice when I turned 18 and registered to vote: I was going to be a Republican. Mine was a Republican household, and there wasn’t much deliberation. I came of age in the Reagan ‘80s and had these extraordinary political experiences. The party was a far different organization at the time, and I was comfortable in it. In the ensuing 30 years, no doubt there were changes in my thinking, and there were definitely changes in the direction of the party. By 2010, when I finally said I needed to [leave the party], I had had enough.

The question was how much of this I was going to discuss on air and in print, because at the time I realized I was no longer comfortable being in a party I thought was veering toward the extreme, the hardcore constituency of both radio and television rewarded [ideological] thinking. Stepping out brought some consequences.

In one of the columns in the book, you write about an encounter with the head of your radio syndicator in which he criticized you for not getting on board with Republican talking points. It seems like, especially in talk radio, that ambivalence is simply not allowed.

My syndicator was very uncomfortable with my independence. During the 2012 election, when we were about 10 days out, Romney and Obama were in a tight race and I had a one-on-one with President Obama in the Oval Office. This was a time when the Benghazi chants were at a fever pitch. I saw a memo that I wasn’t supposed to see circulated by the sales people for my syndicator saying that we really shouldn’t be talking up Michael’s upcoming interview with the president. I thought this was insanity; I get a one-on-one with the commander in chief at the high point of the election, and my own syndicator was outright embarrassed and concerned that I was going to go in there and treat him civilly. They thought this was going to be an anathema to the hundred or so affiliates who were then carrying my program. That was one of those moments when I said terrestrial radio, being on the AM band, is just not conducive to what I’m doing. It was right around that time that Sirius made their first overtures to me.

I have a very definite view of where we are, and I place a lot of blame on the polarized media.

RELATED: How journalism got so out of touch with the people it covers

You write that that both “liberal” and “conservative” lack the nuance to define your worldview. It sounds like a lonely place for an opinion journalist and television pundit to be. So how do you define yourself in 2018?

Independent in my thinking and striving to be evidentiary in my approach. I want to know what the data shows. It is very lonely in the pundit class, but I absolutely believe I speak for the majority of Americans. That’s the irony of this whole thing: We’re being led by individuals who are themselves out of step with society, both opinion journalists and politicians. They’re the outliers. The people I meet when I’m leading my life are a very mixed bag—liberal on some issues, conservative on others, and a whole host of other issues they just don’t have figured out. But if you turn on a television or radio station and listen to the people who are given most of the air time, you would think that it’s the reverse. The data clearly shows that the American people have not become more doctrinaire in their thinking the last 30 years. The parties have moved further apart and things have gotten personal. I know it sounds crazy, but I believe I am the one who is more in the mainstream.

Did Trump’s rise make you question that at all, given that he was outside the mainstream, promoting some pretty fringe beliefs and associating with some fringe characters?

I got the 2016 [campaign] wrong time and again. I thought that every one of his primary and caucus victories would surely be his last, and I’m embarrassed about not seeing that coming. I don’t think Donald Trump would have won the nomination if there had only been two or three or four people on that stage. The fact that there were so many enabled him to harness the hostility that existed among some Republicans. I also think that his nomination was a representation of how many people like me had left the party. But had he not been running against arguably the second-most unpopular major-party candidates—and he was the first—he would not have won.

Trump has been a viewer of your show, and occasionally called you out by name. As a host at a network that’s been on the receiving end of his vitriol, do you worry that his attacks on the press are driving even more polarization?

I worry that he’s been effective in diminishing the credibility of the media among his constituents. The example I’m thinking about specifically is the Russian probe, with his repeated references of this being a “witch hunt” that has been spurred on by “fake news.” The Russia story requires a deep dive. It’s much easier to buy into a two-word sound bite, so I worry about his effectiveness in that regard.

The book is a collection of columns published as they ran at the time, but they each come with an afterword describing how you view the piece looking back. As you went through that process, was there any theme you recognized in your reconsiderations?

I definitely saw a progression in my thinking. There’s no doubt I started in a far more conservative place than I ended up, but I also think that the political climate changed, in particular the Republican party. I didn’t want to just assemble a collection of columns; part of the fun for me was to look back at what I had said, to thump my chest where I got some things right, to lick my wounds where I got some things wrong, and to try to explain through a more recent lens how I viewed those issues. It comes off as a bit of a memoir; it’s a nice snapshot of a post-9/11 world.

The title of the book casts aspersions on each side of the political aisle. Do you feel that, in the current climate, both parties are equally unmoored from the center or the idea of compromise?

They’re both culpable, but at this moment in time, no. There’s a disparity, and more of the uncompromising approach has been on the right. The title is just a reference to the Stealers Wheel song [“Stuck in the Middle with You”], but it would have to be the jokers who are more culpable today if you’re forcing me to choose.

People have got to stop conflating their news and entertainment.

One of the other parties you blame for the lack of moderation in politics is the media. You says we’re guilty of giving more attention to the extremes and ignoring the middle. Has that gotten worse in the Trump era?

No, it’s been a constant. That is one theme I wanted most to come through. As I sat back and took a look at the last 30 years, what I recognized was when I came of age in the Reagan ’80s, 60 percent of the Senate was comprised of moderates. That has all changed, and it has changed in the exact same time period that the polarized media arose. I don’t see that as a correlation; I see that as causation. Primary voters who nominate candidates, especially on the right, are led not by politicians, but by (mostly) men with microphones. That would be OK if their objective was good governance, but it’s not. Their objective is to get people to listen to radio programs, watch TV shows, or click on websites. The partisanship, the polarization that exists in this country today exists for many reasons, but if you ask me to list them, at the top of my list would be the polarized media.

Do you have a theory about when that started?

Absolutely. I would pinpoint the genesis in the early ’90s, when Rush Limbaugh was syndicated. I think of my own experience in Philadelphia at the radio station where I cut my teeth. The lineup of that station, which looked like radio stations across the country, consisted of a guy who was a doctrinaire liberal, an in-house conservative, a libertarian, and Bernie Herman, whose brand was “the gentleman of broadcasting.” If you were a young man or woman today who wanted to be a radio host and talk politics, and you got a sit-down with a program director and said, ‘I want to be the gentleman of broadcasting,’ they would laugh you out of the office.

There was no ideological cohesion among the hosts at that station, nor anywhere else. Then Rush came on the scene when the media was, in a macro sense, left of center. He rolls out the red carpet to conservatives, gets a huge reaction, and stations across the country wanted to have him and a stable of his imitators. I had a front-row seat to watch this process unfold. When it started we had moderation in Washington, and then we started to reward those forces of polarization. As they gained command over primary voters, politicians had to curry favor with them. I have a very definite view of where we are, and I place a lot of blame on the polarized media.

Do you see any fixes for this?

People have got to stop conflating their news and entertainment. The irony is that we’ve never, in our history, had such a selection [of outlets] available to us, and yet so few seem to exercise it. The media today is whatever you want it to be. We’ve got this problem with people being siloed in their news selections. I have no problem with people being mostly one side or the other, as long as you’re sampling everything. I don’t go to bed at night without trying to tap into Hannity and Maddow.

So given the current situation, are you optimistic?

I would love to say that I see change coming, but I really don’t think it changes overnight. I don’t want to inflate my own success, but I would hope that people would look at me and say, there’s a guy not tied to the left nor right, who seems to offend both sides in the span of a one-hour CNN show. I’m trying, by example, to show that you really can be yourself and still cultivate an audience.

ICYMI: CBS’s David Begnaud on covering Puerto Rico when few others did

Pete Vernon is a former CJR staff writer. Follow him on Twitter @ByPeteVernon.