Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

“This is the rarest of rare crimes. It’s a crime that almost never happens. You can say that all you want, and yet, when you listen to it, it does make you look at the world differently, if just for a few days.”

That’s Madeleine Baran, a Minnesota-based investigative reporter at American Public Media. Baran has made a career of muckraking on the web and radio. Before APM, she spent six-and-half years at Minnesota Public Radio, where she documented a cover-up by the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis and won herself a Peabody; she exposed false Medical Examiner testimony and helped get a man out of prison; and detailed the faulty science at the St. Paul police department crime lab.

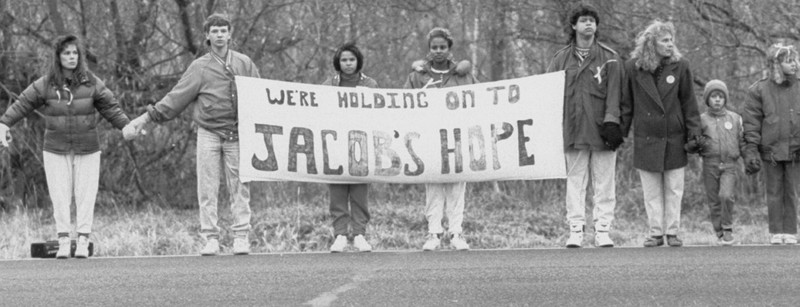

The it to which she refers is “In the Dark,” her 9-part examination of the Jacob Wetterling police investigation. Wetterling was a 11-year-old boy from St. Joseph, Minnesota, who was abducted as he biked to the convenience store in October 1989. Nearly 27 years later, in September 2016, Danny Heinrich confessed to the abduction and murder, and led police to Wetterling’s body.

The podcast, recently named by The New York Times as one the year’s best, hasn’t garnered the fame of “Serial”—to which it is inevitably compared—but it is, for my money, one of 2016’s great achievements in investigative journalism. Baran investigated the investigators, and in doing so she not only exposed the shortcomings of the Stearns County Sheriff’s Office, she also managed to uncover sources whose stories had never been told.

That it’s so good is something of a miracle; remarkably, the series had to be rewritten, and in some instances reconceived, when a person of interest in the Wetterling case confessed. By then, a trailer for “In the Dark” had already been cut and released.

Baran and I spoke by phone.

***

What gave you the idea to do this story; in particular, to investigate the investigation?

Curiosity. I knew a bit about the case just from living here. When you move to Minnesota, people just start saying the name “Jacob.” There’s no last name, no context. People will say, Oh, I just always think of Jacob. It’s hard to overstate how big of a story this has been in Minnesota and how connected people are to it.

I really hadn’t looked into it, so I just had the same generic idea that a lot of people had, which was circular reasoning: The case hasn’t been solved because it’s unsolvable. But then I started to read about the case, just by chance, when I was working on a story about the coverup of the clergy sexual abuse in the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis. The Wetterling case was genuinely surprising because this crime had all these elements that usually point to it being solved: there are witnesses; police got there right away, and there weren’t a lot of places for the person who did it to go. It was puzzling.

Eventually, I decided to test the story out, just do some initial research to see if this question—Why hadn’t the case been solved?—had already been answered. I didn’t know what the answer would be.

At the end of Episode Nine, you say: “The perfect crime is just an excuse for the failures of law enforcement, and we buy it, but really there are no perfect crimes. There are only failed investigations.” That is unnerving, especially if you write about crime, because you assume a baseline of competence. Do journalists just have to be far more skeptical?

In general, of course. If we can’t prove something, we shouldn’t write it. Or we should explain that we can’t prove it. But for the most part, nothing should be taken for granted. In this case, you had what looked like a lot of detective work, and it was. The quantity of work was obvious. There were TV crews showing people working 20 hours, working nonstop. Investigators weren’t seeing their families. A lot of them were living away from home in hotels in the area.

But some basic questions weren’t asked: Did you talk to the neighbors? Did you secure the crime scene? Instead of assuming that the problem—if there is a problem with the case—might involve something really high-tech, we first checked the basics. I don’t think that had been questioned much here, and it makes me wonder how many cases are similar to this one—presented as an unsolvable, epic mystery, with the most basic police work undone.

At the beginning of Episode One, there’s audio of a September 6 press conference at which it was announced that Danny Heinrich confessed to the abduction and murder. At the time of this press conferences, the podcast was essentially done, right?

Yes. I started my reporting in the fall of 2015. I had done some initial reporting before it was revealed that Danny Heinrich had been arrested, which happened in late fall of 2015. In late July and early August of 2016, I did the final interviews, including with the sheriff, where I laid out what we had found. It was a couple weeks after my interview with the sheriff that Danny Heinrich confessed to the crime in court, which was the day of that news conference.

At that point, we had already released a trailer of the podcast and a summary online. We’d said that we were going to ask, Why hasn’t this case been solved? We were not, we said, going to solve the case. We had several episodes completely done. We were editing the later ones when he confessed. We had planned to be done, maybe mixing, maybe making some final edits to some later episodes. Instead the news overtook it, and us.

That was a surprise, I take it.

Yes, but we knew that it was possible. The hope was, if Heinrich did it, that he would confess because they had him on these federal child porn charges, and he might be motivated to get a good deal. We knew that his trial date was approaching.

I’d done a lot of backgrounding of Heinrich and a couple other people who I knew were at the top of the list of suspects. But before the confession, we hadn’t really settled on how to use that information, because we weren’t going to say, Here’s who did it. What if Heinrich hadn’t done it? But when he confessed, we’d already done all the work, so it was just a matter of figuring out how to use it and the significance of certain details based on what he said in court.

Having to scramble to re-edit and re-envision the project must have been a pain in the ass. But on the upside, you were given a fair amount of clarity.

We had a list of however many mistakes law enforcement had made, but which ones really mattered? That’s something we didn’t know. To be able to say, Well, all these people who saw a blue car, that really mattered. To realize that, in fact, Dan Rassier had seen the abductor’s car, was significant. He was a witness who’d been turned into a suspect.

We were able to incorporate a lot of the older material. And we could get rid of the stuff that we now knew wasn’t significant. But it also helped us tell Dan Rassier’s story. We believed he did not commit the crime, and we wanted to tell the story of his life being ruined without fueling speculation that he did it. That was something that weighed very heavily on us.

To have that burden lifted, so that we could say, Look, he’s a person who’s been wronged, and you don’t have to take our word for it that he did not do this, was a big relief as a journalist.

At what point did you decide Danny Heinrich was the best suspect?

We never decided that, actually. Because we were not trying to solve this case. That’s not why we were there. We felt that it was certainly possible that Danny Heinrich committed the crime. He had no alibi, and there were a couple other things, but there was no proof that he committed this crime, and we weren’t looking for it. It was definitely possible to me that he didn’t do it because I didn’t have access to all of the investigative file or to the complete list of other suspects.

The one issue we really hadn’t resolved was how to handle this guy. Before the confession, we knew that if we put him in the podcast and make a big deal out of him, that would imply something we don’t mean to imply—that we think he did it. On the other hand, how do we not include this?

I imagine there a lot of lawyers involved, parsing the story’s language.

With all of our investigative work, we have a lawyer we work with. But with Heinrich, we were never going to say, Yeah, we think he did it. All the evidence points to it being him. That’s just not true. There was not very much evidence that we were aware of, one way or the other. In fact, the one episode we hadn’t written before the confession was the story of Jared, the Paynesville boys, and Heinrich, because we were not sure if it was at all significant. Because if it wasn’t Heinrich, does any of that matter [in the context of the failure to solve the Wetterling case]? No. We didn’t even have a draft. We just were not sure what to make of it.

Were Patty and Jerry reluctant to do this? It’s obviously a painful thing to relive.

They were very generous with their time. Their focus was finding their son, and Patty is very much a public figure. She’s ran for Congress. She’s a national advocate for child safety, so she talks to a lot of reporters about child safety, about her son’s disappearance. I called Patty Wetterling very early and just said, Hi, this is who I am. I’m thinking about reporting on this, before I was even going to report on it. And I asked if there was any reason why it would be a problem to investigate and report on this.” She said, “No, go for it.”

You talk about Jacob’s life early in the story, literally from the womb. Oftentimes crime stories focus on the perpetrator at the expense of the victim.

We thought that was important, and I think there’s a way in which people become obsessed with elevating the criminal into some sort of fascinating truth teller. It’s a convenient thing when the case doesn’t get solved because they could say, Well, see, the criminal’s just too smart. There’s a danger of missing the harm in what actually happened. That’s why we opened the podcast with Jacob.

When you were preparing for this story, how much of a premium you put on the old news stories? Because you didn’t have access to trial transcripts and open case files to give you the skeleton of the narrative. There must’ve been hundreds of disparate sources.

That was perhaps the greatest single reporting challenge. Because it was an unsolved case, we could not get the case file. It wouldn’t have all the answers, but there’d be a structure of the investigation; this happened on that date, the names of the officers, etc. Instead, I read every single news story in Westlaw that had ever been written about the Wetterling case. Then, our associate producer, Natalie [Jablonski], found all archival radio stories and TV news stories.

I interviewed the former police chief of St. Joseph, it’s a small town, and his wife said to me, “Oh, I’ve just been cleaning out all these old videos.” She had taped of all the early Wetterling coverage—the first three weeks—and was about to throw it out. There also was stuff the Wetterlings had in their basement that they had taped and thrown into some boxes in the crawl space.

We looked for as much TV and radio coverage, and local radio coverage as we could find. Then we created a long list of people to interview, including all the former law enforcement who were still alive. In cases where they weren’t, was someone in their family still alive that could point us in the right direction of something? We talked to a lot of people who helped us construct the story from the outside of the file.

How many people did you interview?

Hundreds of people. We did a lot of reporting on stuff that we didn’t really need just to make sure things were correct. We did a lot of interviews that we never put in the podcast.

The reporting for it was full-time from fall of 2015 through the summer of 2016, with some additional reporting after the confession. But we felt that was the amount of time that was needed to understand it; if we weren’t going to commit to doing the right amount of reporting, we had no business doing this story.

How did you learn about Jared Scheierl? Was that a matter of public record? The reason I ask is he sounds like he’s telling his story for the first time.

He had been out there and given some interviews by the time that we started reporting. But I am a big believer, with this type of long-form reporting, that even when you think someone has told a story before, you don’t assume they’ve told the best or complete story. So we did some very long interviews with some of the main people in our story. I know we got to parts of the story that hadn’t been told before, and I think part of it was just a matter of taking the time to go through the story more slowly than they had before.

One thing Jared said, which I felt was profound, was how he got others to tell their stories: “You start with your own story.” It made me wonder: how you got people to open up to you.

I’m pretty minimal in interviews. I think most people do want to tell their stories, and we just need to be good at listening. We were able to say, Hey, we’re going to be at this for a really long time—months and months—and so let’s take our time with this. We got to know these people pretty well over the course of the reporting.

How do you maintain your calm when people tell you about the worst thing to ever happen to them?

I’m always very conscious of the fact that I’m not the person this happened to. That’s a boundary I am going to respect. I’m not going to try to step on somebody else’s grief. As difficult as this story might be for me to hear, it is the tiniest of tiniest compared to experiencing it. That’s how I think of it. This is my job.

You are not there because this is something that happened to you. You’re there because this is a story that needs to be told, and this person is trusting you to tell it.

Of course, you also don’t want to seem callous either. You have to strike a balance.

That’s true. I guess I’m not reacting in the same way that I would if a friend told me this story. But I also wouldn’t be reacting like, Next question, because that’s not what I’m thinking, either. You follow your own instinct as a reporter and as a human listening to a story of trauma.

I’m also a big believer in, Let’s take a break. Try to be attuned to the dynamics of the interview and if it’s getting too intense. If it’s getting too intense for me, that’s probably a sign that it might be very intense for the person who’s actually experiencing it.

But I think it would be a mistake to elevate my experience very much. It’s tough, of course, but I could choose to not do this. This is a job, after all.

A couple of weeks ago, Eli Saslow said, “As I’m reporting, I’m always thinking about structure,” meaning he is very conscious of what he needs as far as the narrative. This came to mind when you were with Dan Rassier, walking on his property, and you find police tape. Because it was perfect. Were you conscious in the moment, or at any moment during “In the Dark,” that something would make a really good scene? Or an I ascribing too much premeditation here?

No, you’re not. I wanted to go and see this for myself, just for the reporting, but we knew that it could be a really good scene, depending if we did find any crime scene tape. Also, what we wanted to capture was his world. This is where he likes to be, out in the woods, clearing brush. This is what he does. We knew that was a scene that we would want.

I think about structure very early on in a story. I end up revising the structure a thousand times in a longer story, to the point where the beginning structures does not bare any resemblance to the end. You need to be thinking about what the story is and constantly challenging yourself.

In the first episode, you have that wonderful metaphor of these ever-expanding circles. Is that something you came up with, or was that a law enforcement metaphor?

No, that was my own view. That’s how I made sense of the crime. I thought of it as a circle from the very beginning when I just thought about it in my own mind. I talked to editors about it, and explained, Here’s Jacob with the abductor. I draw a circle around it and then just imagine it expanding slowly that night, and that’s why they have to respond so fast.

When I visited the site [of the abduction], there was something about this moment in time, when the crime had just happened and everyone was arriving. 15 minutes ago, you could point to a specific spot and say, That’s where Jacob was. And 15 minutes later, he wasn’t even that far away.

I figured, “Why not just share that image?”

Knowing what you know about the crime itself, if law enforcement had done everything right, would they have caught him? Would they have gotten to him in time to get Jacob alive?

I don’t know the answer to that.

There was this wonderful symmetry in the first and last episodes. In Episode One, the sheriff’s department in their announcement uses the word “closure.” Then, in the Update, the Wetterlings explicitly refute the idea. Seems like one of those wonderful symmetries that you couldn’t possibly plan for.

Right, although we did intentionally ask that. I did ask them about closure because that interview was after the confession and closure had been so much on the mind. It’s what people were talking about.

It’s always interesting to me, the difference between the experience of the people involved and everyone else, like Jerry Wetterling says in an interview with me, “Well, maybe it’s closure for some people. Maybe it’s closure for you. Maybe it’s closure for law enforcement, but it’s not closure for us.”

To that end, in Episode 9, you talk about the need for more transparency, to show people what actually is being done in investigations. What’s the balance to strike between that and necessary privacy, and between the needs of journalists and law enforcement, especially if the case is unsolved?

That is a challenge because it’s not as though it makes sense to say, “Well, why are all these case files closed?” Because it’s a really bad idea to just be walking around with open case files for your unsolved crimes, as a general practice. Does the suspect want to find out how close they are to catching him? He could just go look at the records or have a friend do it and see when they’re planning to come question him. Clearly that is not a viable option.

I talked to a bunch of experts in criminology about how there are no mandatory standards in how to proceed in a lot of these cases. You just have to imagine how things unfolded, because there’s no [mandatory] checklist; Did we canvas the neighborhood? Did we secure the crime scene?

“In the Dark” is so complicated. There are so many strands and locations and characters. What was your method for keeping all this straight?

My method for organizing investigative reporting is pretty basic: Just put everything on a timeline. I just have a Word document that starts out on one page, “Jacob Wetterling was born on this day, Jacob Wetterling’s kidnapped on this day.” And then, as I continue my reporting, that timeline grows and grows. The timeline encompasses everything.

I put basic big-world or national or local news events on the timeline as well, so it starts to get more detailed. Maybe something happened on a particular day in 1985 and it was a huge news story, which would explain a great deal about how people reacted. I’ll put major events. I think my timeline now for the Wetterling story is more than 400 pages, and it starts with Lewis and Clark exploring the area in the 1800s. Which is not something that was used, but I just wanted to have everything on there.

Can you give me an example of how this was useful?

The method of organizing a story was helpful when Heinrich confessed. All I had to do was just do a word search for “Heinrich” from my timeline. Every detail from the backgrounding of Heinrich was already there, so I could see him in relation to the Paynesville cases. He was on probation at the time. This is when he dropped out of high school. This is when something significant happened with the Wetterling family. I could just extract it, and it was in chronological order.

The other thing I’ll do is sketch or outline how the story will break down and just constantly revise that. We had a document that was revised constantly. Everything is scanned. Everything is organized in folders. All the audio is transcribed, and then at a certain point over the summer, we printed all our interview logs and put the papers into binders and then just disappeared off in our own little sections for a week to just read them.

Whether it be the Wetterling investigation or the story of the archbishops, can you see a throughline in your work? Is there something that drives you, some commonality?

My job as a reporter is to find out things that people would have most likely never known about otherwise. In terms of the content, a lot of my reporting has been about institutions that have a very particular type of culture that doesn’t lend itself well to transparency and accountability—the Archdiocese, the sheriff’s office. There are all kinds of things that they do not want you to know.

My work as an investigative reporter is to find out facts that are being covered up but, through my reporting, answer the questions, What is it like inside this thing? Why is it this way?

Reporters, I think, have to take a much more skeptical view of police investigations. But it’s one thing for somebody like you, who’s got the time to take a granularly critical view of a case, but what about guys who are on the cop beat and have to file five stories a week? They probably, to some extent, take what the police say as Gospel because that’s all they’ve got time to do. Is it just a worthless beat, because they are not skeptical enough?

I don’t think it’s a worthless beat at all. Those are the people that know everybody in the police department, if they’re doing their job right. I had to learn all that stuff. I wasn’t a journalist who reported on the Stearns County Sheriff’s Office, so I was at a disadvantage going in. I didn’t know any of these people.

I’ve been a general assignment reporter before, so I know what it’s like to be in a situation where you have half a day or an hour or 15 minutes to figure something out. It’s challenging. I think that some of the questions are pretty basic, though, and not necessarily time consuming. For instance, Did you canvas the neighborhood? I don’t know why we were the first people to reveal that, 27 years later. It’s not a high-concept question.

On the other hand, there were people doing really good reporting on that story in the early days. A really good reporter on a police beat knows a lot of people, but also has a variety of sources, so they’re not going to be shut out completely if they tell the truth. There will always be people who want the truth to be told.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.