In 1977, at the age of twenty-five, Seyoum Tsehaye dropped out of college to join the fight for Eritrea’s self-rule. He knew how to use a camera; the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) tasked him with documenting the war. From the front lines, he captured the bloody struggle for freedom during its moments of honor and despair. When the EPLF revealed troubling edges, he showed that, too—much to the dissatisfaction of his compatriots, who threw him in prison for a year without a trial. In 1991, when Eritrea declared independence, Tsehaye continued his work as a photojournalist, collecting images of his people’s first steps in a sovereign country.

By then, Eritrea, tucked in the Horn of Africa on the border of the Red Sea, had been under colonial control since the late 1800s (by Italy, Britain, then Ethiopia). Under its first president, Isaias Afwerki, the transition to independence proved difficult. Tsehaye became the founding director of Eri TV, the state broadcaster, but it was not long before he was demoted, to a position in the ministry of tourism—the powers that be didn’t appreciate it when he aired coverage critical of the government. Over time, Afwerki fell deeper into totalitarianism—growing paranoid, failing to implement a constitution, refusing to hold elections—and Tsehaye began freelancing for Setit, an independent news outlet, where he reported on women’s rights, HIV, and disabled veterans. In 2001, as part of a wider push for democracy in Eritrea, Tsehaye published a piece in Setit urging the regime to support its people. Authorities responded by mandating that independent newspapers be shut down across the country. Tsehaye and other outspoken Eritreans were imprisoned.

Ever since, the press in Eritrea has been effectively shuttered: “a dictatorship in which the media have no rights,” as Reporters Without Borders has described it. Tsehaye has remained behind bars. But this year, a sign of hope appeared with the launch of 2001 Magazine, started by Seyoum Tsehaye’s twenty-four-year-old niece Vanessa.

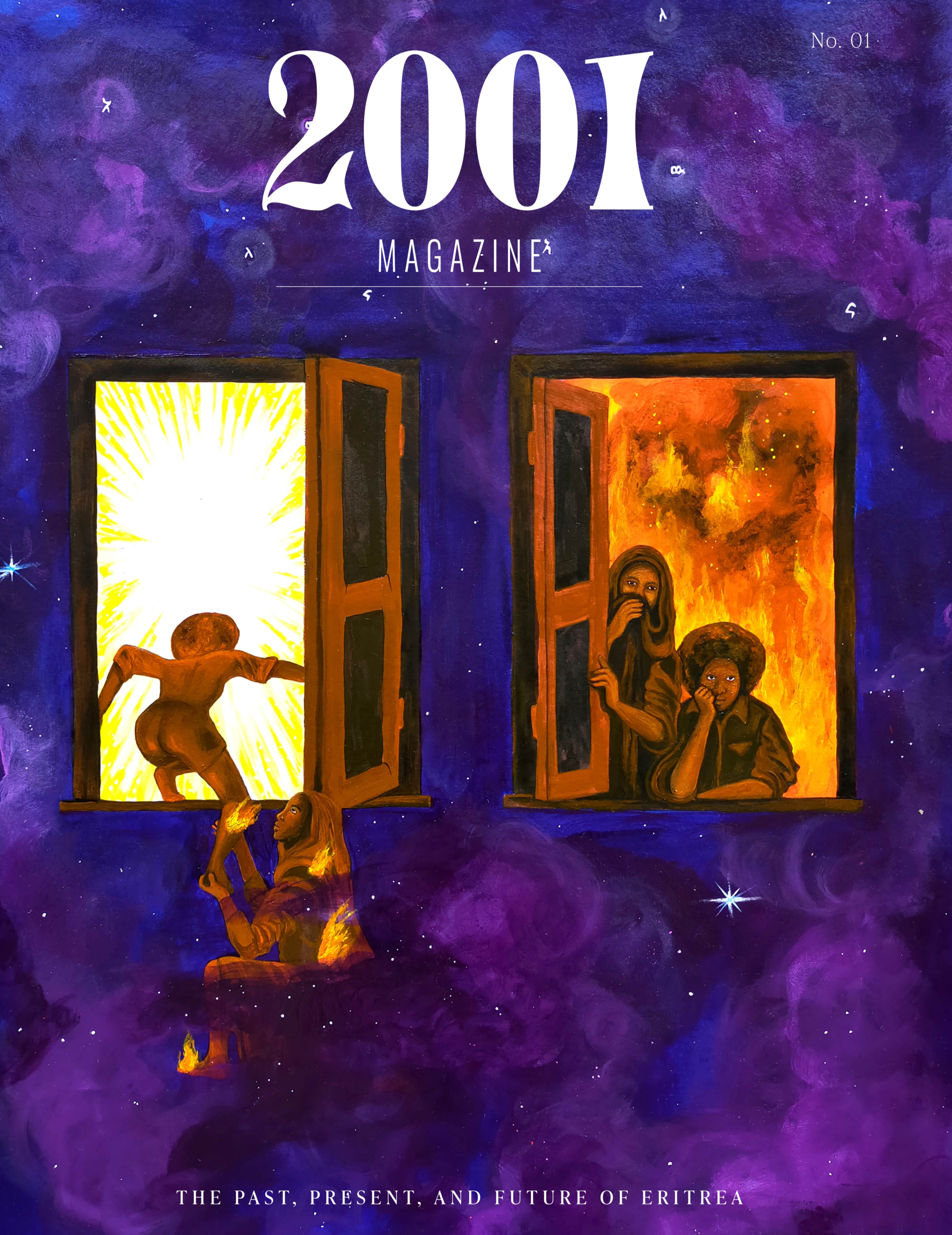

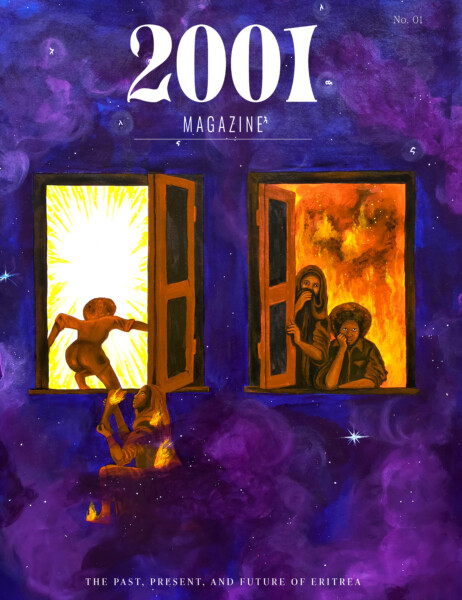

Named for the year the Eritrean press was dissolved, 2001 was produced by Vanessa Tsehaye’s organization, One Day Seyoum, which advocates for the release of those imprisoned by the government. The inaugural issue reveals the challenges of Eritrean life, in pieces rendered without access to on-the-ground reporting. “We’re used to working with a country like Eritrea,” Vanessa Tsehaye said, “but we wanted to create the foundation for people who wanted to learn more.”

VANESSA TSEHAYE FIRST LEARNED about Seyoum, her mother’s brother, while growing up abroad, in Sweden. Her mother wanted her to know about the family back home. “She would just tell us, ‘This is this uncle; this is that aunt; they have three kids’; and for him—Seyoum—she just at some point was like, ‘And he’s imprisoned, but he hasn’t done anything wrong.’” The situation was hard to understand. When Vanessa was in high school, her bafflement grew into frustration. It was then that, along with some friends, she formed One Day Seyoum, to organize against Afwerki’s regime—and, as she put it, to “do what I was criticizing other people for not doing.”

The idea to start a magazine came several years later, when the staff—all volunteers, based around the world—was discussing a social media campaign to profile each year of the dictatorship. It occurred to Vanessa that their research could fill a zine. “In Eritrea, we don’t even know when things get worse or better, because people are so scared of speaking that it’s really hard to get breaking news or any kind of story that could help raise awareness,” she said. “So we have to think quite creatively.”

Courtesy of 2001 Magazine

Through investigations, interviews, essays, art, and poetry, the resulting magazine explores a theme of “Past, Present, and Future.” There is a piece on Afwerki and the EPLF’s earliest signs of despotism; another details the methods by which the regime has maintained a stronghold on its overseas population (namely, a dreaded 2 percent tax). A story on military conscription describes the conditions at a remote facility called Sawa, which the United Nations has deemed slavery-like. In an article called “Tattoo on My Brain,” Aaron Berhane, the former editor in chief of Setit, recalls driving through Asmara, Eritrea’s capital, after authorities announced an end to independent journalism. He describes his staff meeting for what would be the last time. “Sometimes I wonder how we even survived for four years,” he writes. (Berhane died in May, in Toronto, at the age of fifty-one, from COVID-19 complications.)

Given the government’s ban on local reporting, 2001 relied heavily on members of the diaspora, who represent between a third and half of all Eritreans. “We were able to use people’s testimony and experiences as a source,” Sienna Jacob, an Eritrean-American based in London, and the issue’s editor, told me. Their accounts reflected the views of people who left the country at different times, yet they shared a sense of connection in their pursuit of a better life. A profile features the work of Meron Estifanos, an Eritrean journalist and activist living in Sweden, who has been a resource for refugees making the perilous journey through North Africa’s migrant corridors; there’s a conversation with Daniela Yohannes, who created the artwork for the magazine’s cover. “I want to confront the truths of our past—even if violent or painful—because I want to understand what I am the result of,” Yohannes told 2001.

“A lot of the information in the magazine is quite sad and tough to read,” Jacob said. But it’s also imaginative. “I think issues like this seem hopeless and, you know, people might not think about aspiring for the future,” she continued. “It’s important for people to realize that this isn’t it, and there’s things that can be done.”

SEYOUM HAS NOT BEEN seen or heard from since he was detained. Vanessa has no way of reaching him, to send him a copy of the magazine or just to talk. Contacting Eritreans inside the country poses a challenge, too—2001 is being sold online and in print, but anyone who might try to buy a copy inside the country would face dangerous repercussions if they were found out. Vanessa said it’s not worth the risk; she’s focused on the audience of Eritreans abroad.

In the coming years, 2001 plans to release new issues annually. “Our role is to mobilize the diaspora,” Vanessa said, “to create an informed and engaged diaspora to support efforts at home.”

Feven Merid is CJR’s staff writer and Senior Delacorte Fellow.