Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

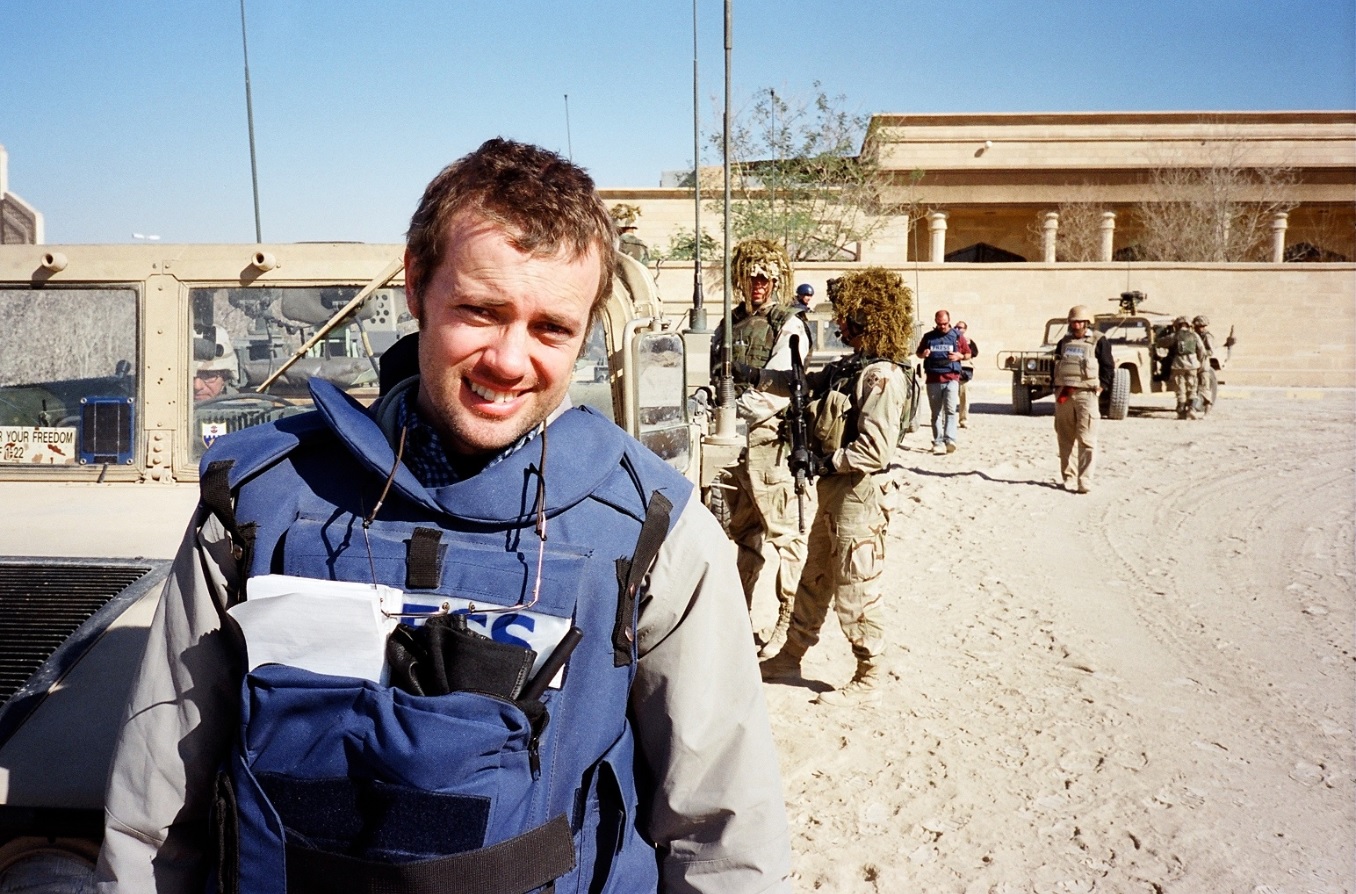

Dean Yates encountered and documented plenty of tragic events over 20 years as a journalist with Reuters, from a nightclub massacre that killed 202 in Bali to a tsunami in Indonesia that killed 165,000.

But of everything he’s seen, two deaths haunt him most: Those of his Iraqi staff members who were gunned down in the streets of Baghdad in July 2007 by US soldiers riding in an Apache helicopter. Namir Noor-Eldeen, a 22-year-old photographer, and Saeed Chmagh, a 40-year-old driver, had gone to East Baghdad after hearing reports of an American airstrike in the area. There, they were hit and killed by raining gunfire along with at least 11 other people.

Details of what happened that day would come to light several years later when Wikileaks released gunsight footage of the attack, taken from onboard the Apache, with the crew’s radio chatter as its soundtrack. “Once you get on ‘em, just open ‘em up,” a crewmember says, confirming a command to shoot. Namir and Saeed can both be seen in the gunners’ sites with cameras slung over their shoulders, walking among a loose cluster of men, before the shooting begins. “Oh yeah, look at those dead bastards,” a pilot says, when the helicopter circles back around. “Nice,” a crewmember replies.

ICYMI: Local news suffers a tremendous loss

Yates was Reuters’ Baghdad bureau chief at the time of the attack. It was his job to confirm the deaths, to be there for the staff in their grief, and to investigate what happened. It wasn’t until days later, left alone in his office, that he finally wept. And it wasn’t until years after that he began to understand the full impact of the deaths on his conscience.

A doctor in 2016 diagnosed Yates with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. He was living in Tasmania with his family, in a beautiful village far removed from any fighting, when the accumulated horror he’d witnessed, and the guilt he felt over the deaths of Namir and Saeed, finally surfaced. That summer, he entered Ward 17, the PTSD unit at a psychiatric hospital in Melbourne.

That’s when Yates started thinking about helping other journalists. “The idea started to emerge, that maybe when I recovered, maybe I could do something for my industry,” he told CJR.

In May, Yates took on the position of mental health and wellness advocate at Reuters, a position that would allow him to blend his decades of experience as a journalist, correspondent, bureau chief, and top news editor with the particulars of his journey with PTSD, to address the spectrum of mental health and wellness issues in the newsroom. Reuters has 2,500 journalists globally that could potentially benefit from the program.

***

COLLEAGUES DESCRIBE YATES as considered, energetic, effective; a man you trusted to be in charge. “He was so efficient and so on top of things,” said Mike Williams, the global enterprise editor at Reuters, who met Yates in 2011 and later would edit a feature story Yates wrote for Reuters about his struggle with PTSD.

In those days, you gave the tough assignments to those who could handle them, and debriefed them when they got back, says Paul Holmes, a global politics editor for Reuters until 2007. “I never even for a moment considered the sort of psychological impact that this might be having on me,” Yates says.

So it came as a surprise to Yates himself, and to some of his colleagues, when symptoms began to emerge: He was irritable, reacted to loud noise. Some days he couldn’t get out of bed. “When I got stressed, I was flung back in time to our office in Baghdad, as if I had never left. I would bang my fists on the desk, scream at the walls,” Yates wrote in his story for Reuters.

He couldn’t shake the death of his two colleagues.

“I’ve been reliving that day every day for the past 18 months,” Yates tells CJR. He took several months off work after the diagnosis, and spent the time unpacking the memories of the previous two decades. As July rolled around, and with it, memories of Namir and Saeed, Yates began what he calls “a forensic examination” into his actions at the time.

He printed out all of his email correspondence from that period, reading and rereading them. He called friends, Iraqi colleagues, predecessors, other foreign journalists, and tried to piece together what he could have done differently.

“I was responsible for the safety of my staff,” said Yates. “I felt that I had failed them as bureau chief.”

Journalist Dean Yates pictured in his study at his home in the town of Evandale, located near the city of Launceston in Tasmania, Australia. Reuters photo by Cameron Richardson.

He felt guilty he had not been fully familiar with US rules of engagement, which allowed the military to open fire if weapons were visible—even if no fighting was taking place. Whether the helicopter crews had indeed followed the rules of engagement is still up for debate: Wikileaks deemed the incident “collateral murder,” while a military investigation found no fault in the soldiers’ actions. In the video, crewmembers claim to see AK-47s and RPGs, but even a careful viewing leaves some doubt as to whether the soldiers mistook the cameras for weapons.

Yates felt particularly guilty that when the Wikileaks videos came out in 2010, he did not get involved in the story for Reuters, despite having been closest to it. He happened to be on vacation in Tasmania at the time, and didn’t want to face the emotions he knew it would bring. “I was cowardly when WikiLeaks released that video,” he would later write. “That’s something I have to live with.”

Whatever Yates was looking for in the process of his forensic examination, he wasn’t finding it, and it was making his condition worse. Later that summer, he entered Ward 17. There, Yates would come to realize that something more than PTSD was at play in his case—a fairly new concept called moral injury.

ICYMI: NBC journalist’s harassment allegations revealed. Less than 24 hrs later, a disturbing tweet.

The term was coined in the 1990s by Dr. Jonathan Shay, a psychiatrist who worked extensively with veterans suffering from PTSD. Shay has since said that PTSD alone rarely wrecks veteran’s lives. “Moral injury—both flavors—does,” he wrote in the Psychoanalytic Psychology journal in 2014.

“It looks like this kind of moral injury acts as an accelerant for PTSD and other psychological problems,” says Bruce Shapiro, director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism. “And it is also highly associated with burnout, and with ethical problems in reporting.”

It is not, however, considered a recognized disorder or a mental illness.

A 2017 study on moral injury by International News Safety Institute surveyed journalists who covered the Syrian refugee crisis. It found that moral injury was more prevalent among respondents than PTSD or depression. A 2015 study by the researcher Klas Backholm surveyed journalists who covered the Anders Breivik murders in Norway, during which close to 100 people were murdered. The results revealed higher instances of PTSD or depression among journalists who also felt guilt over perceived ethical breaches—either their own, or their employers’—during the events.

For Yates, learning about moral injury was a revelation, especially because he’d initially had difficulty accepting his diagnosis. “How could I be suffering so much and yet, I hadn’t even really been on the front lines?” Yates had asked himself. “It took me some time to really understand that I had a lot of PTSD symptoms, but it was really moral injury crushing me.” It helped explain why he continued to feel responsible for the deaths of Namir and Saeed, despite being assured repeatedly by friends and colleagues that he was not to blame.

After being discharged, Yates wanted to share what he knew, first by sharing his own story, and then by taking on the role of advocate.

“He’s not telling his story because he wants people to think about Dean Yates,” says Holmes, who stayed in touch with Yates over the years. “He’s telling his story because he sees an issue that needs to be addressed.”

***

IN WARD 17, Yates met many other frontline professionals, including firefighters and police officers who were suffering as he was. He learned that many of the men and women he met weren’t getting proper professional support, and he wanted to see that change for journalism.

Journalism as an industry has come a long way in acknowledging and addressing mental health issues in the workplace. A 2002 study by Dr. Anthony Feinstein, a Canadian psychiatrist who had previously worked with veterans, was one of the first to study the incidence of PTSD in journalists. He found that of 140 war journalists, 19 percent had some symptoms of PTSD. Feinstein’s work, concurrent as it was with 9/11 and the Iraq war, led many newsrooms to add resources for dealing with the aftermath of traumatic events.

By the early aughts, for example, many large newsrooms implemented 24/7 crisis hotlines, including the BBC, the Associated Press, and CNN. Newsrooms also provide debriefing sessions, self-assessment tools, and training to prepare journalists for the security and emotional risks of reporting from dangerous places.

As approaches and policies in the newsroom continue to evolve, experts stress that one crucial area to address is building resiliency as a preventative measure, rather than reacting after the fact.

“The literature shows that the most protective factor for people in frontline professions is not access to clinical help, though that’s important sometimes,” Shapiro says. “It’s actually social support and peer support.”

Reuters already had some mechanisms for trauma support in place before Yates came on. In 2006, the company established a crisis hotline for journalists, a service Yates made use of after the deaths of his staff. In 2015, the company implemented a Peer Network of trained volunteer journalists who are available and reach out to colleagues in tough situations.

Yates is aiming to build on those initiatives by fostering a culture of openness and awareness from staffers. They should talk openly, and managers should be proactive in offering support. “I want to really break that stigma down and create an environment where journalists feel comfortable about those sorts of stuff.”

Reg Chua, executive editor at Reuters, said he sees parallels between the security protocols the company has put in place and the expanded wellness initiative. “If you have some kind of real injury, we’ll clearly take care of it, but the whole goal is to not have that injury in the first place.”

Yates said there’s one memory of the support he received that’s stayed with him.

On New Year’s Eve in 2005, days after a tsunami hit in the Aceh province in Indonesia, Yates got a message to call Holmes, the global politics and general news editor, who was back in New York. It had been a harrowing few days. “It was death and destruction on an unimaginable scale,” says Yates.

I thought the best thing I could do was call everyone who was covering that story, even those I had never met, and just ask them how they were doing.

On his first day in Banda Aceh, the largest town in the province, he walked into a mosque where stacks of bodies had been collected. “I just thought, I need to count these bodies,” Yates said. There were over 150 of them. It had been several days since the wave hit, and in the heat of Indonesia, they were beginning to decompose. “I just felt someone had to count them.”

When Yates reached Holmes on his satellite phone, the editor said something along the lines of, “We just want you to know how proud we are of the work you’re doing, and we just want everyone to know, tell everyone there that we’re thinking of them.”

Yates wasn’t the only one who got the call. “There was such overwhelming trauma and grief involved in that story,” Holmes recalled, that he got a list of reporters on the ground, and stayed up until the early morning hours trying to reach reporters across Asia. “I thought the best thing I could do was call everyone who was covering that story, even those I had never met, and just ask them how they were doing.”

Holmes said that was hardly standard practice back then. But having been a journalist himself for decades, he knew what it was like to be in a foreign country, facing inconceivable horror and tragedy.

Yates emphasised that a big part of his role will be to encourage practices that can be crucial for all journalists working in high-pressure environments, even if they’re not anywhere near conflicts or humanitarian crises: things like meditation, yoga, exercise, and learning to switch off.

Shapiro said that the literature on resiliency backs him up that wellness supports resiliency. “Having a work life balance turns out to be very important in the resilience of people in frontline professions,” says Shapiro. “It’s not just a touchy feely thing.”

***

YATES SPENT the 10th anniversary of the deaths of Namir and Saeed back in Ward 17. In the weeks leading up to it, he felt himself slipping and knew he couldn’t face that day alone. He spent a week writing a 5,000-word long letter to Namir and Saeed, exploring his complex feelings of guilt, shame, and grief.

“That allowed me to take the next step which was to try to heal from it,” says Yates. “I still have days when my anxiety is off the charts. There is no cure for PTSD or moral injury; it’s how you manage it.”

What concerns Yates most is those who don’t have the kind of support he does.

ICYMI: Plagiarism scandal hits local newspaper

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.