Here is the usual path for an aspiring sportswriter: start by covering high schools. Think crosstown rivalries. Homecoming games. Friday night lights. After a few years, you’ll get a shot at the bigtime college and pro beats.

Mick McCabe didn’t do it like that. He’s covered high school sports for 49 years and counting—a remarkably rare run, and not only because he spent his entire career at a single news outlet, the Detroit Free Press.

From the archives: Two sportswriters find success crowdfunding

Detroit is home to four major league teams, and it’s in the shadow of two top Division I schools. McCabe dabbled in covering them, taking an extended West Coast trip with the Detroit Tigers, for example, and reporting on University of Michigan football during its first Rose Bowl victory under legendary coach Bo Schembechler.

But McCabe made prep coverage his priority. Given the severely restricted media access at the higher levels, he says, this is where you’ll find the better stories.

“High school kids are great,” McCabe says. “They’re honest—they haven’t learned to lie to the media yet. I thought, This is much better.”

More than just longevity, McCabe’s sportswriting is pioneering for its kid-first approach and its expansive coverage of female athletes. For his work of nearly half a century, McCabe was inaugurated into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame in October, cueing a spate of reflections on a career that began in an inner-ring suburb of Detroit.

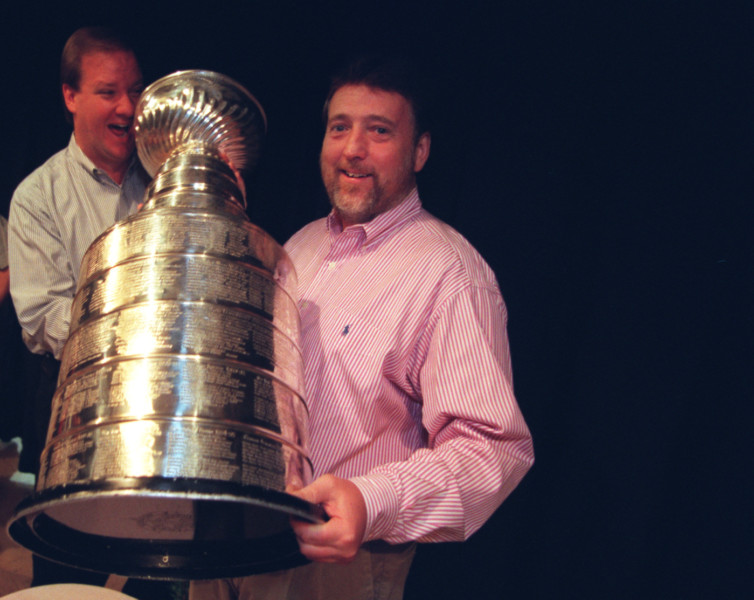

Former Free Press Detroit Red Wings beat writer Bill Roose (left) and Mick McCabe hold the Stanley Cup in 1997. Courtesy of the Detroit Free Press.

McCabe grew up in Allen Park, where he still lives, a block away from his boyhood home, and he worked on the newspapers at his Catholic high school and college. In June 1970, when he was 21 years old, McCabe got a gig as a copy boy at the Free Press. He also assisted Hal Schram, a longtime prep sportswriter who was nicknamed “Swami,” with his column that predicted the outcomes of big basketball games. (The name, which rings uncomfortably, references a male Hindu teacher, which Schram was decidedly not.) McCabe covered games himself, and soon started selecting top athletes to feature on the Freep’s All-Catholic, All-Suburban, and All-Metro football and basketball teams.

McCabe never stopped making high school sports his focus, but his side coverage gave him a foot into the wider world of sports, including Magic Johnson’s early years at Michigan State. His familiarity with Detroit prep basketball made him a key contributor to the team covering a booster scandal that impugned the University of Michigan’s basketball program.

But, “it just wasn’t for me,” he says. “So many people equate self worth with the beat they’re covering. It doesn’t make you any better just because you’re covering the Pistons or the Lions or the Tigers.” Though after saying this, he quickly gave a nod to the talent of his colleagues who follow these teams.

When Schram died in 1987, McCabe took over the column, which has been in print more than thirty years with his byline. Under McCabe, the column began making calls on football games for the first time; to further distinguish himself from his predecessor, McCabe began using lighthearted nicknames for schools, bringing a touch of humor to a beat that can be consumed by self-seriousness.

McCabe’s more lasting legacy, though, is reimagination of prep coverage as a beat that centers young people and is harsh on coaches and administrators who don’t do the same. “When I started in the early ‘70s, everything was coach-driven,” he says. “They were the only ones quoted in stories. No one was talking to the kids. I thought, This is nuts, and started interviewing players.” Even now, McCabe says, reporters usually quote the coach and other top-level officials in their stories before getting around to young athletes. “I try to go the opposite of that,” he says. “The kids start the story.”

McCabe interviews Harrison High School head football coach John Herrington after a game last month in Farmington Hills, Michigan. Courtesy of the Detroit Free Press.

He’s also alert to the unique dynamics of covering athletes who are generally minors. Unless they are the best in the state, or there is some other mitigating factor that puts them under the spotlight, “you don’t mention a kid’s name in the Free Press after he misses a shot or fumbles a ball,” McCabe says. It might be the only time in his life that he might get his name in the paper. “I’m not interested in humiliating any kid.”

McCabe and the Free Press also took girls’ sports more seriously, relatively, than their peers. He dates this to a 1976 showdown dubbed “Operation Friendship” between two high-level girls basketball teams in the Catholic and public school leagues. After witnessing a dramatic fourth-quarter comeback and raucous chants in the stands—a fan culture that had developed on its own, wholly outside the media’s eye—it dawned on him that “there was this whole audience that we weren’t appealing to.”

The paper began covering girls’ high school basketball and expanded to other sports, as well as women’s college teams. “Everybody was just ignoring girls’ athletics, so we were kinda pioneers.” The statewide Miss Basketball award is now named for him.

He also breaks the football-basketball binary by spotlighting other sports, including swimming, soccer, cross country, and wrestling. That’s what led to early Freep features on, for example, Allison Schmitt, an eight-time Olympic medalist. He also discourages competitive parents from making their kids “specialize” in a single sport, an approach he models in his work.

Besides dispatches from the sidelines, McCabe wrote more expansive stories on athletes who struggled with eating disorders or were teen parents. Three top high school baseball prospects in the Detroit area gave him a chance to examine the decline of African-American participation in the sport. When a drunk driver killed a football player in St. Ignace in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, McCabe drove more than four hours north to cover its impact on the community. “I didn’t even ask the sports editor,” he says. “I just got in my car and drove.”

So many people equate self worth with the beat they’re covering. It doesn’t make you any better just because you’re covering the Pistons or the Lions or the Tigers.

McCabe’s versatile reporting made him only the fifth sportswriter to be inducted into the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame in 2014. He got to the point where he was averaging 400 stories a year—a mix of features, columns, and his weekly picks. While the high school beat made it possible for him to not be away from his family as much—a priority for him—“the hardest thing was missing their games because I was going to write about someone else’s kid.”

“I was always exhausted, especially the last 10 years,” McCabe says. In 2016, he accepted one of the buyouts that Gannett offered the staff. But after doing a couple freelance stories for The Athletic, his Freep colleagues reached out to him, saying, as McCabe summarized it, “If this moron is still writing, he should write for us and not The Athletic.” McCabe had left a glaring gap on its pages, since Gannett “hadn’t allowed them” to hire someone else to fill his position. The news outlet went from the best prep sports coverage in the state to scarcely any coverage at all.

McCabe agreed to a part-time deal. That’s how he’s come to be back on the sidelines, even in semi-retirement. His articles still have unusual reach.

“I know every story I write is going in somebody’s scrap book,” he says. “It’ll be read years and years and years from now”—by a spouse, he says, or by grandchildren. “I’d feel horrible if they read it and thought, ‘This guy just mailed it in.’ Every single story was important to these kids. That’s kind of my motivation to do as good a job as I could.”

ICYMI: Time for a new game plan for covering high school football

Anna Clark is a journalist in Detroit. Her writing has appeared in ELLE Magazine, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Next City, and other publications. Anna edited A Detroit Anthology, a Michigan Notable Book, and she was a 2017 Knight-Wallace journalism fellow at the University of Michigan. She is the author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, published by Metropolitan Books, an imprint of Henry Holt. She is online at www.annaclark.net and on Twitter @annaleighclark.