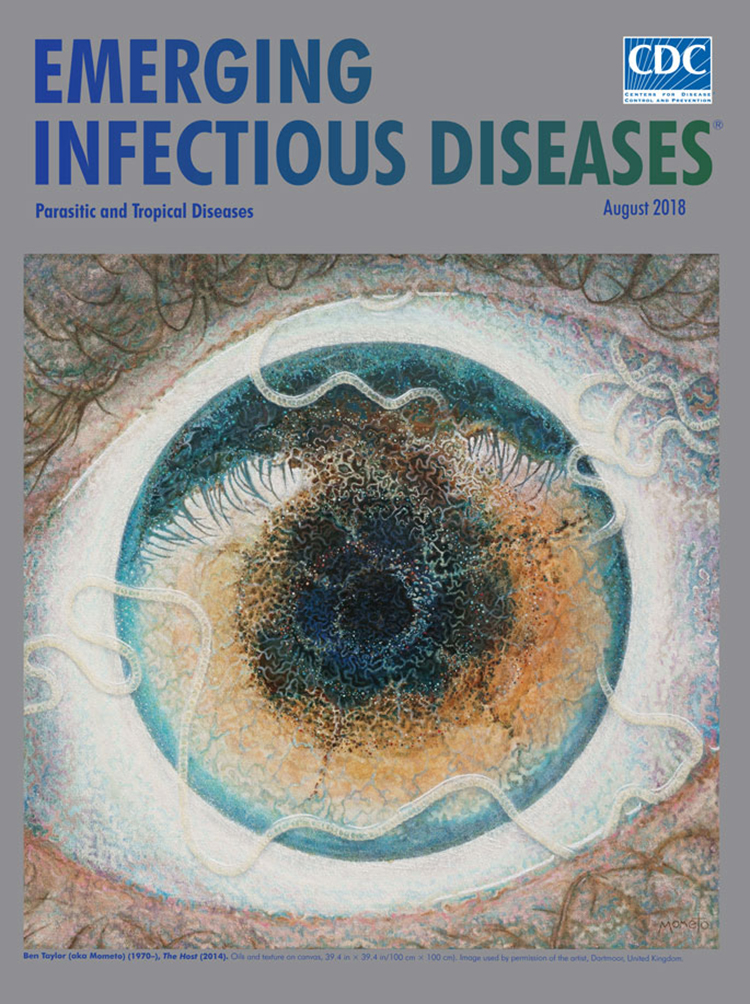

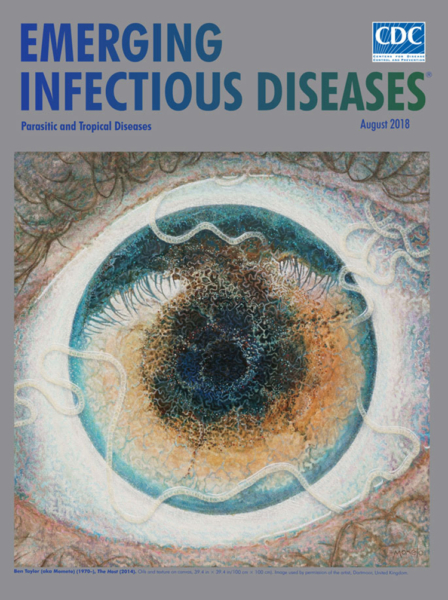

In August, an image of a painting by the British artist Ben Taylor called The Host went viral. It was a self-portrait of sorts, though an unconventional one: a striking close-up of an eyeball with a pale, translucent worm slithering on and beneath its surface. Taylor completed the painting after he discovered that an inch-long roundworm had, horrifically, taken up residence in his eye during a trip to Gabon a couple of years earlier.

Image courtesy of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The painting stood out not just for its grisly backstory, but also because it happened to have been featured that month on the cover of Emerging Infectious Diseases, a journal published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

EID—which, like the agency, is based in Atlanta—is funded by the CDC (at a cost, in 2018, of nearly $2.8 million, the agency affirms); it has no advertising, and subscriptions are free. The peer-reviewed journal publishes more than 500 articles per year and accepts, on average, only a quarter of all submissions, which come from virtually every country on earth.

ICYMI: “It’s almost like having a robo-freelancer pitching a story”

The journal always chooses its covers to accentuate the material inside, a collection of grim reports and seemingly abstruse charts that give scientists worldwide a forecast of what’s to come in the world of infectious diseases. The August issue’s theme was “Parasitic and Tropical Diseases.”

“The goal is not to be playful or cute or to attract attention,” says D. Peter Drotman, the editor in chief of EID. “It’s to humanize the content and to say we’re dealing with an issue that affects humanity in many ways. One way that humanity has expressed itself is through art and how it deals with the human condition and suffering.”

It’s a surprisingly abstract sentiment for a publication whose dispassionately worded articles, with titles like “Evidence for Previously Unidentified Sexual Transmission of Protozoan Parasites,” don’t leave much room for metaphysical interpretation. But the magazine, which was founded in 1995, takes this mission seriously.

Since 2001, the journal has published art on the cover of every issue, a practice initiated by Polyxeni Potter, one of EID’s founding editors. Her aim was to bear out the connection between art and public health—a connection with a rich history, going back to da Vinci’s famed anatomical studies—and she accompanied each cover with a short, explanatory essay at the end of the magazine. The column was a welcome relief from the publication’s otherwise clinical content, a palate cleanser in the vein of The Economist’s heartwarming back-of-the-book obituaries. (In 2013, Potter’s essays were collected in a book called Art in Science: Selections from Emerging Infectious Diseases.)

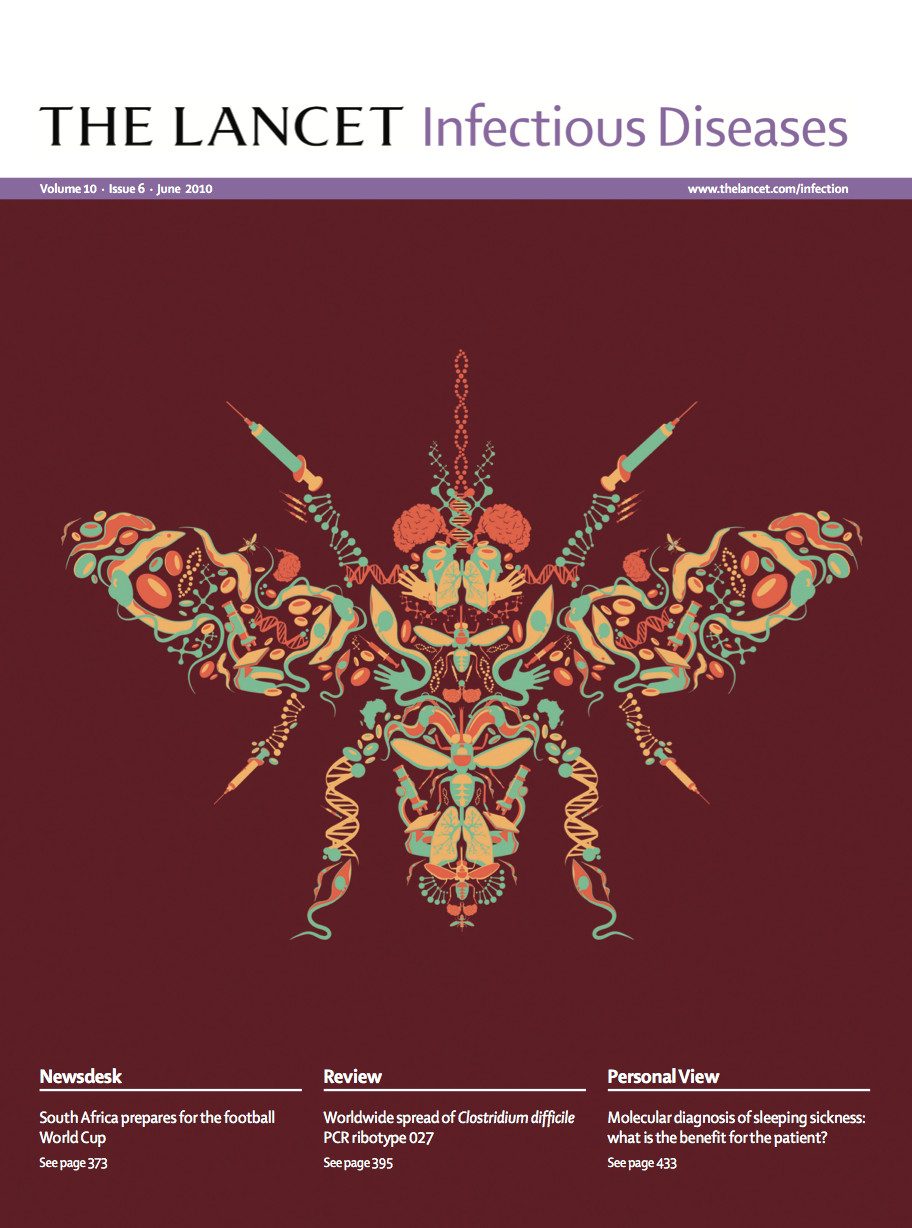

EID isn’t the only journal in the world of infectious-disease publishing to put art on its covers. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, for instance, holds annual contests to choose an artist to create original covers inspired by the journal’s articles. The Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society has been using children’s art on its covers since its inception in 2012. And Clinical Infectious Diseases features disease-related art—paintings, statues, architecture—on its covers.

Showcasing art offers a way to enhance visual appeal and to attract people to the public-health information inside each issue, editors at these journals say. Some have more specific motivations: “It was decided that featuring children’s art would be an optimal way to engage the next generation,” explains a former JPIDS cover editor. The genesis of the trend, however, can perhaps be attributed to the Journal of the American Medical Association, which began using fine-art covers in the 1960s under the direction of an art-enthusiast editor in chief. In the 1970s, cover selection fell to longtime JAMA editor Therese Southgate, whose masterstroke was to include an eloquent, page-long essay in each issue, giving some art history along with her own feelings about the work she had chosen. Southgate’s essays were an unlikely hit, appealing to physicians and lay readers alike, and they’re now collected in three separate volumes, published between 1996 and 2011, called The Art of JAMA.

“I’m trying to show that everything is related: art, medicine, life,” Southgate said in a 1999 interview with The New York Times. ”Physicians and other people in the field can enjoy art, whether it’s medical or not.” (Southgate died in 2013.) After a redesign in 2013, JAMA stopped regularly publishing art on its covers, and so EID, with its thoughtful cover curation and charming essays, has perhaps more than any other scientific journal continued Southgate’s legacy.

Byron Breedlove, who has been the journal’s managing editor since 2014, is now in charge of choosing art and writing most of the accompanying essays, a responsibility he approaches with care. “When Peter assigns the cover theme,” he says, “I go through a period of, usually, panic to try to think about how I’m going to find things.”

Breedlove, who has worked for the CDC since 1987, takes an ecumenical approach to cover selection, featuring a wide variety of art from different cultures, geographic areas, and periods in history. “We are biased in favor of artwork that depicts humans, and particularly humans interacting with animals,” says Drotman, who has helmed EID for 17 years and previously worked in preventive medicine. “That’s an important route by which infectious diseases emerge.”

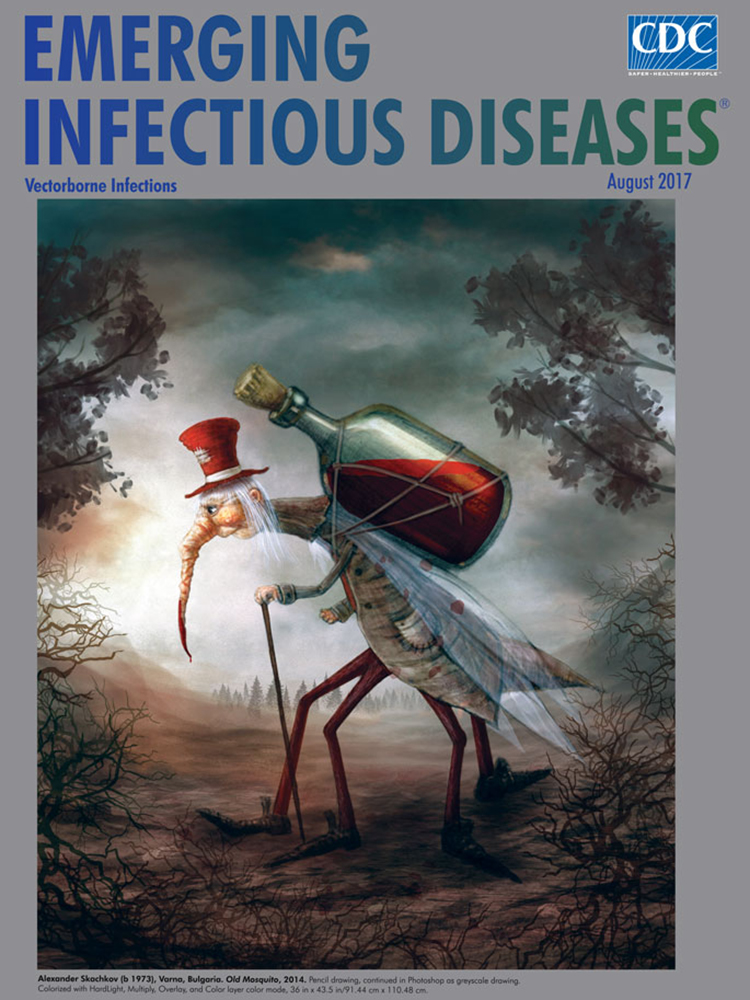

In terms of tone, the covers are alternatingly stark (Nicolas Poussin’s 1630 oil painting The Plague at Ashdod graced the cover of the January 2018 issue, “High-Consequence Pathogens”), playful (Picasso’s Don Quijote was a complement to “Zoonoses” the next month), and creepy (Alexander Skachkov’s 2014 painting Old Mosquito was a visual stand-in for “Vectorborne Infections” on the cover of the August 2017 issue). (Images below.)

“In this clever image, Skachkov depicts a tired older mosquito heading home after a long night of collecting blood,” Breedlove notes in his accompanying essay, which he cowrote with Paul M. Arguin, an associate editor of EID. “The bare branches and grayish fog of morning suggest that summer is past and the old mosquito is approaching the end of his days in the end of the year. The bright red blood contained in the mosquito’s jug, his red hat and legs, and, of course, his blood-tipped proboscis tinged from its hematophagous endeavors, contrasts with the morning gloom.”

Though the journal is mostly read by public-health professionals in the field, with just under 5,000 print subscribers, it appears to have something of a niche following among art and literary types, who appreciate the magazine for its beautiful covers and dismal content.

Alexis Rockman, a visual artist who says he’s a fan of EID, and whose paintings have been featured by the journal, says he finds the covers “kind of goofy,” but he appreciates them nonetheless, comparing the journal’s design approach to Harper’s Magazine, which frequently features fine art on its covers. “Anything that appreciates art, I’m all for,” he says, “because in America, unless you’re talking about auction prices, no one cares about art.”

Dwight Garner, the New York Times book critic, says he’s been a subscriber for a few years now, though he admits that he doesn’t read the magazine in its entirety. “I look forward to the day it arrives, reading the ghoulish headlines aloud to my wife,” he writes in an email. “They sound even more terrifying in the magazine’s restrained academese; they’re like NOAA weather broadcasts, just the facts.”

“The covers are almost always great,” Garner adds. “Emerging Infectious Diseases livens up a coffee table, for sure.”

Matthew Kassel is a freelance writer whose work has been published by The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Slate.