Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

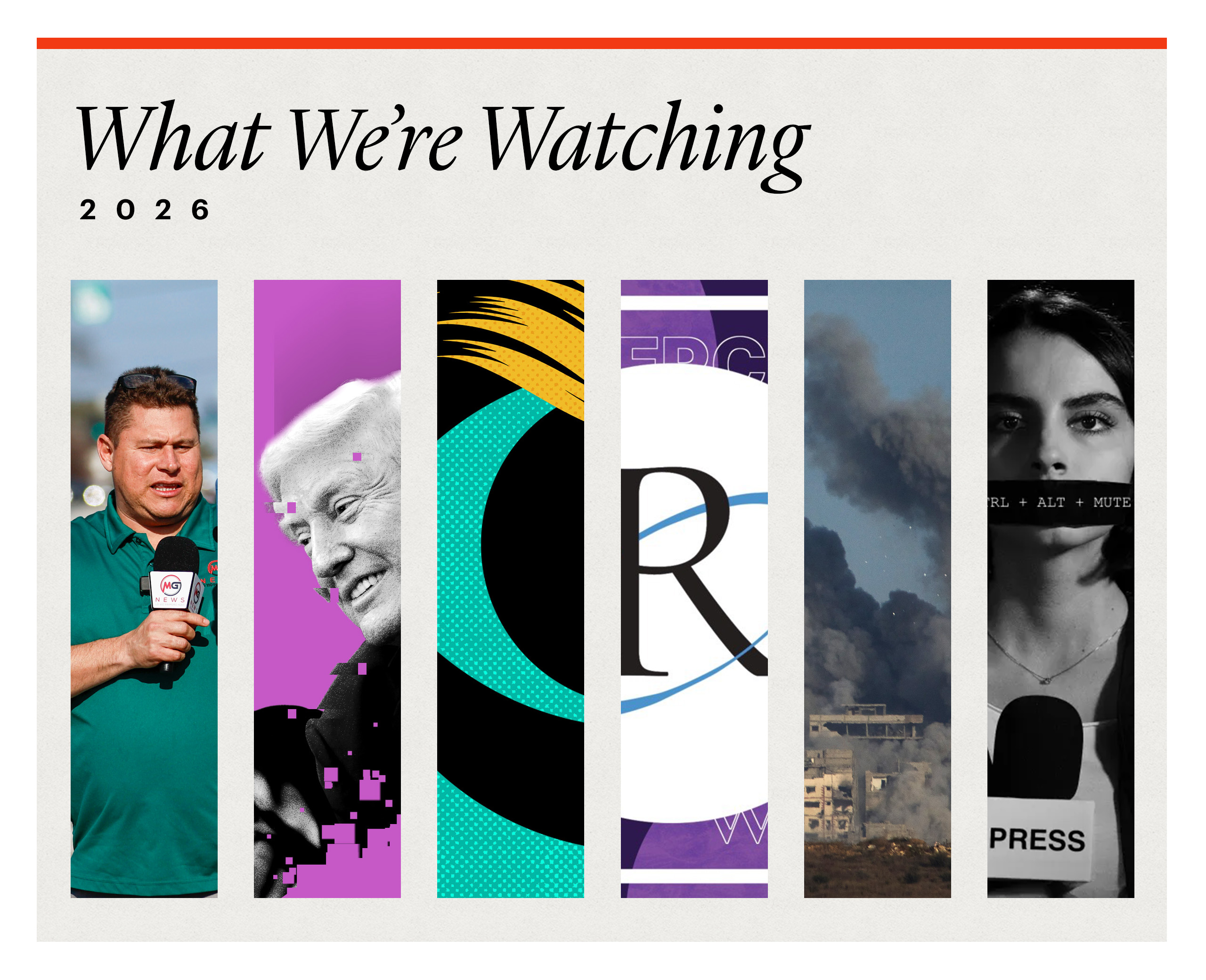

Last year, Immigration and Customs Enforcement deported Mario Guevara, a journalist from the Atlanta area who since 2004 had been reporting on immigration primarily for the local Spanish-speaking community. Guevara, age forty-eight, is originally from El Salvador, which he’d left because he had received death threats for his journalism. In June, he was picked up by police in Doraville, Georgia, while covering a “No Kings” protest against Donald Trump—an action widely seen as retaliation for his reporting. His case marked a devastating blow to press freedom in the United States. This year, I will be watching anxiously to see what else might happen along these lines, and what precautions journalists take to avoid the worst. —Betsy Morais, editor in chief

Journalism is in a crisis of credibility. Young people in particular experience the process of finding good information as confusing and overwhelming, and this leads them to distrust journalists. A recent survey by the News Literacy Project found that 84 percent of teens, for example, have negative views of the media that include seeing journalism as “fake,” “false,” and full of “lies.” This problem is not without a solution. Teens and people everywhere do desperately want access to good, accurate information—especially given the state of online media channels that are cluttered with corporate interests and AI slop. In this way journalism is more valuable than ever. The online ecosystem surfaces plenty of bunk, but it also rewards a rarer commodity: sincerity and authenticity. Journalists who believe in what they do, and who are unafraid to be loud about it, will stand out. —Camille Bromley, contributing editor

As 2025 wound down, President Trump’s lawyers filed a ten-billion-dollar libel claim in US District Court in Florida, alleging that a BBC documentary that aired in late 2024 defamed him by misleadingly editing a speech he gave that preceded the assault on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021. The BBC acknowledged its error and sent an apologetic letter. Two leaders resigned. But Trump was not mollified. Legal experts have called his legal claim bunk and say he can’t win in court. But he doesn’t need to. All he needs to do is avoid summary dismissal so he can use the suit as leverage, as he has already done with ABC and CBS, extracting large settlements in both cases. How forcefully will the BBC resist? The answer matters enormously, because by forcing the BBC to capitulate, Trump could achieve multiple objectives, further undermining independent media in the US, weakening the BBC’s position with the British public ahead of what will be a contentious debate over its future funding, strengthening his political allies in the United Kingdom who have been trying to crush the BBC for years, and further eroding the entire system of public media, as seen in the successful effort to defund NPR and PBS in the US. I’ll be watching where this goes, because the whole global information system hangs in the balance. —Joel Simon, contributing writer and director of the Journalism Protection Initiative at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism

Over the course of the past few months, conflicts between universities and student journalists have escalated, leading to the closure of some print editions of student publications, the firing of a university-hired media adviser, and, in one case, at the University of Alabama, the closure of identity-focused publications out of concern that they might clash with President Trump’s take on diversity, equity, and inclusion. Student journalists, press freedom organizations, and supporters are rising to meet the challenge through vocal opposition, legal letters, and donations. As tensions escalate, I’ll be watching university actions and responses to them across the board this year to see which schools toe the line and how the defense of student journalism evolves. —Riddhi Setty, Delacorte Fellow

In 2017, I declared the first ill-fated “pivot to video” dead in a Nieman Lab prediction, though I really should have known better. Like all sweeping and misguided media trends, it’s back. This time it’s podcasting that’s pivoting, driven by familiar promises from platforms: better ad rates, broader reach, and deeper engagement.

Derek Thompson recently argued that “everything is television now” (defining television very broadly as “the continuous flow of episodic video”), but it seems obvious that it shouldn’t be (and I say that as someone who makes and loves TV). There’s also little evidence that’s actually what audiences want. In 2025, YouTube reported that it has more than a billion podcast viewers a month, although “viewers” may be a bit of a misnomer: a recent survey on podcast consumption in America suggests that nearly half of those users are primarily listening. On Spotify, which is making a big push into video, that number rises to almost 70 percent.

Video often makes sense for talk shows, where production is fairly minimal and costs are relatively low. But some of the best podcasts are narrative or investigative features that aren’t inherently visual and won’t be served by essentially being turned into documentary films. I’ll be watching to see if and how the podcast industry can withstand the pressure to make everything video. I’d argue that it never makes sense to focus on formats instead of making good work and trusting the audience to find what’s worth reading, watching, and, yes, listening to. But like I said, I’ve been wrong before. —Susie Banikarim, contributing writer

They infiltrated the White House press room early in 2025, and now they have the Pentagon press corps for themselves—what’s next for “new media,” a/k/a the MAGA press? During his first term, Donald Trump fought relentlessly against legacy media, and in his second coming, he’s found a way to replace them: right-wing news outlets, influencers, and podcasters are enjoying the warm embrace of government officials, echoing their talking points instead of scrutinizing them. So far, Trump and Pete Hegseth have failed at silencing “traditional” (oh, how it hurts to put it in scare quotes!) journalists, and that should continue to be the case. But I’ll be keeping an eye on what they use their newly installed media figures for. (And I will keep an eye on Hungary, where I’m from: in April, Viktor Orbán, an established enemy of press freedom, might be out of his job.) —Ivan L. Nagy, Delacorte Fellow

Last year was a notable one for arts criticism. Vanity Fair let go of Richard Lawson, its chief critic; the Associated Press stopped reviewing books; the New York Times reassigned veteran critics to other jobs. For New York, Charlotte Klein wrote about whether media organizations still want cultural criticism; Spencer Kornhaber, a staff writer for The Atlantic, questioned whether the traditional review still has a place in mainstream media; and in the New York Review of Books, Matthew Aucoin argued that the decline of criticism as it previously existed could actually be a good thing. “It isn’t easy out there; these days it’s even harder to find steady work as an arts writer than as a performing artist,” Aucoin writes. “But since the old newspaper-centric model of warmed-over hot takes has crumbled—and since it was never so great in the first place—why not go deeper?” I’ll be watching how arts sections in newspapers continue to change and evolve over the coming months. —Carolina Abbott Galvão, Delacorte Fellow

How much damage will President Trump’s wrecking ball inflict on US democracy? And can the press rise to the moment in covering it? This is what I’ll be watching domestically as 2026 unfolds. Since retaking office last year, the Trump administration has deployed federal troops to US cities against their will. It has had people detained and disappeared to other countries. It has bombed boats in the Caribbean that human rights groups call extrajudicial killings. It has expanded executive power and stamped on congressional oversight. With the midterms in November potentially taking away the Republican clean sweep of the executive branch, House, and Senate, I’ll be watching how the news media covers Trump’s authoritarian creep. Will his pressure campaign on publishers and news networks mean some begin to keep their heads down and blunt the blade of their scrutiny?

Internationally, I’ll be watching what happens if and when reporters gain access to the Gaza Strip. How many bodies could be found under the rubble? What atrocities might be uncovered from the nearly two-year war? Trump talks up his credentials as a peacemaker. But if peace means anything, it’s much more than just the absence of war; it is also the dispensing of justice. And it is justice that Trump, and other world leaders involved in Gaza’s new International Stabilization Force, must be judged on. —Jem Bartholomew, contributing writer

In 2022, when Qatar hosted the World Cup, outlets like The Guardian took it as an opportunity to look beyond soccer and dig into the mass-scale labor exploitation that underpinned the whole tournament. This summer, as the World Cup comes to the United States (alongside cohosts Mexico and Canada), will the swarming international reporters likewise seize the chance to report beyond the tantalizing spectacles of the tournament and try to capture this bizarre American moment for their home audiences? Could the tournament serve as a launchpad for some genuinely great general reporting? As Gianni Infantino—the president of FIFA, the governing body of the World Cup—continues to shamelessly sidle up to President Trump, there should be no shortage of off-the-pitch stories to tackle. Just this month, during a pretournament event, Infantino dramatically bestowed Trump with the “FIFA Peace Prize–Football Unites the World” award—an accolade FIFA invented in November. —Amos Barshad, staff writer

According to research commissioned by UNESCO in partnership with the International Center for Journalists, nearly three-quarters of women journalists worldwide report work-related online violence, and a quarter say those attacks escalate into explicit threats of physical harm, including death threats. Many survey respondents described threats of sexual violence, doxxing, and coordinated smear campaigns. In East and Southern Africa, recent reporting using the UNESCO study described these attacks as “part of everyday life” for women journalists (and often for their family members). Gendered and sexualized abuse pressures women to self-censor, abandon certain beats, or leave journalism altogether. The figures come from “The Chilling,” a yearslong global study, rather than from a single 2025 poll, but they form the basis of UNESCO’s 2025 campaigns against AI-amplified gender-based abuse.

Although the UN stresses that tech-facilitated gender-based violence violates the right to freedom of expression, media freedom, privacy, and equality, and often evolves into offline attacks, online attacks are still tracked and reported far less systematically than killings, imprisonments, and physical assaults on journalists. In 2026, the question will be whether newsrooms, platforms, and regulators will treat these harassment campaigns against women journalists as the targeted violations of press freedom and equal participation in public life the UN says they are, rather than as a calculated cost of being visible online. If they fail to step up coverage, the cost is fewer women’s voices, less women’s editorial curation in journalism, and narrower public debate. —Amanda Darrach, producer

I’ll be watching to see if America’s shrinking press can find new ways to counter the expansion of the Overton window and slow the acceptance of unacceptable acts by governments and billionaires. One of the best ways to do this is by zigging when others zag, not covering what everyone else thinks is the story and instead continuing to look without blinking at one spot after others have moved on. In our current muzzle-velocity news cycle, this old technique is more useful than ever; remember that you are recording history, not just filing for today and tomorrow. Solidarity—that elusive thing among fractious journalists—is another radical act that will benefit both the press and the public. —Vanessa Gezari, contributing editor

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.